The USV Story: Domino Effect

Back to back like Tim Duncan in '03. The finale.

Previously:

Early 2000’s NBA was the league’s most talented cohort.

Top to bottom, there were killers everywhere.

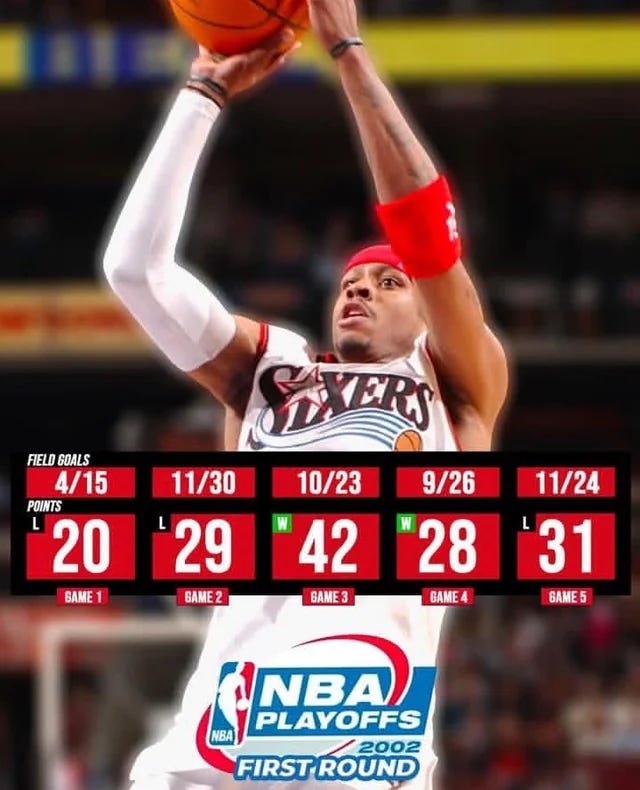

Allen Iverson led the league in scoring during the 2001-2002 season with 31 points per game, then came Shaquille O’Neal at 27, Paul Pierce at 26, Tracy McGrady at 26, Tim Duncan at 26, and Kobe Bryant at 25.

Vince Carter, Dirk Nowitzki, Chris Webber, Karl Malone, Ray Allen, Gary Payton, Kevin Garnett, Michael Jordan, Steve Francis, Peja Stojakovic, Rip Hamilton, and Jerry Stackhouse are just some of the guys who averaged at least 21 points per game.

Playoffs were a bloodbath.

The West was anchored by Kobe and Shaq on the Lakers, Peja Stojakovic and Chris Webber on the Kings, Tim Duncan and Tony Parker on the Spurs. The Mavericks had Steve Nash and Dirk Nowitzki, the Timberwolves had Kevin Garnett. In the East the Pistons had Jerry Stackhouse and Ben Wallace, the Celtics had Paul Pierce and Antoine Walker, and the New Jersey Nets had Jason Kidd, runner up for the MVP award in 2002.

The Sacramento Kings and Los Angeles Lakers 2002 Western Conference Finals matchup was one of the most controversial series in all of NBA history. This series was singlehandedly responsible for people waking up to the possibility of “rigged sports leagues”. The Los Angeles Lakers were coming off a back-to-back championship run and were, by no close margin, the biggest draw in the league. It did not take a McKinsey consultant to conclude that having Kobe and Shaq compete for a three peat would mean higher ratings and more money for everyone involved. The Sacramento Kings, on the other hand, were a new style of basketball. Mike Bibby, Chris Webber, Peja Stojakovic, and Vlade Divac played more like elite European teams than traditional NBA squads. They moved the rock and it didn’t matter if Webber had 20, if Peja had 20, or if someone else got hot. After 5 games of play, the Kings were up 3-2, with a chance to send the Lakers home in Game 6.

The Lakers shot 40 free throws, almost twice as many as the Kings’ 25 attempts from the charity stripe. They won Game 6 106 - 102. To the Lakers credit, Shaq did make an unprecedented amount of free throws - the big fella went 13 for 17 from the line. The Lakers would go on to win Game 7 as well, advancing past the Kings to the championship round. Years later, Tim Donaghy, an NBA referee convicted of fixing games, claimed that two of the referees involved in Game 6 “acted to extend the Lakers-Kings series to Game 7” under pressure from the league’s executives. While the Lakers ended up on top after sweeping the Nets, the regular season MVP went to Tim Duncan, who narrowly edged out Jason Kidd for the award.

Duncan’s quiet persona and unassuming dominance perfectly matched the San Antonio Spurs organization.

The LA Lakers were Hollywood. Kobe and Shaq were like Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio in the same movie - a fiery duo with violent offensive upside and equally tumultuous locker room issues. Kobe’s fadeaway buckets over double teams made the crowd gasp in disbelief while his missed game winners caused the same crowd to grieve. Shaq would rip the rim off the backboard then miss four free throws to follow. Without a doubt, the Lakers were the best team in the league with Kobe and Shaq, simultaneously the most loved and the most hated. Kobe and Shaq carried the purple and gold torch that Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, and Jerry West passed down from generation to generation. The Lakers were showtime, for better and worse.

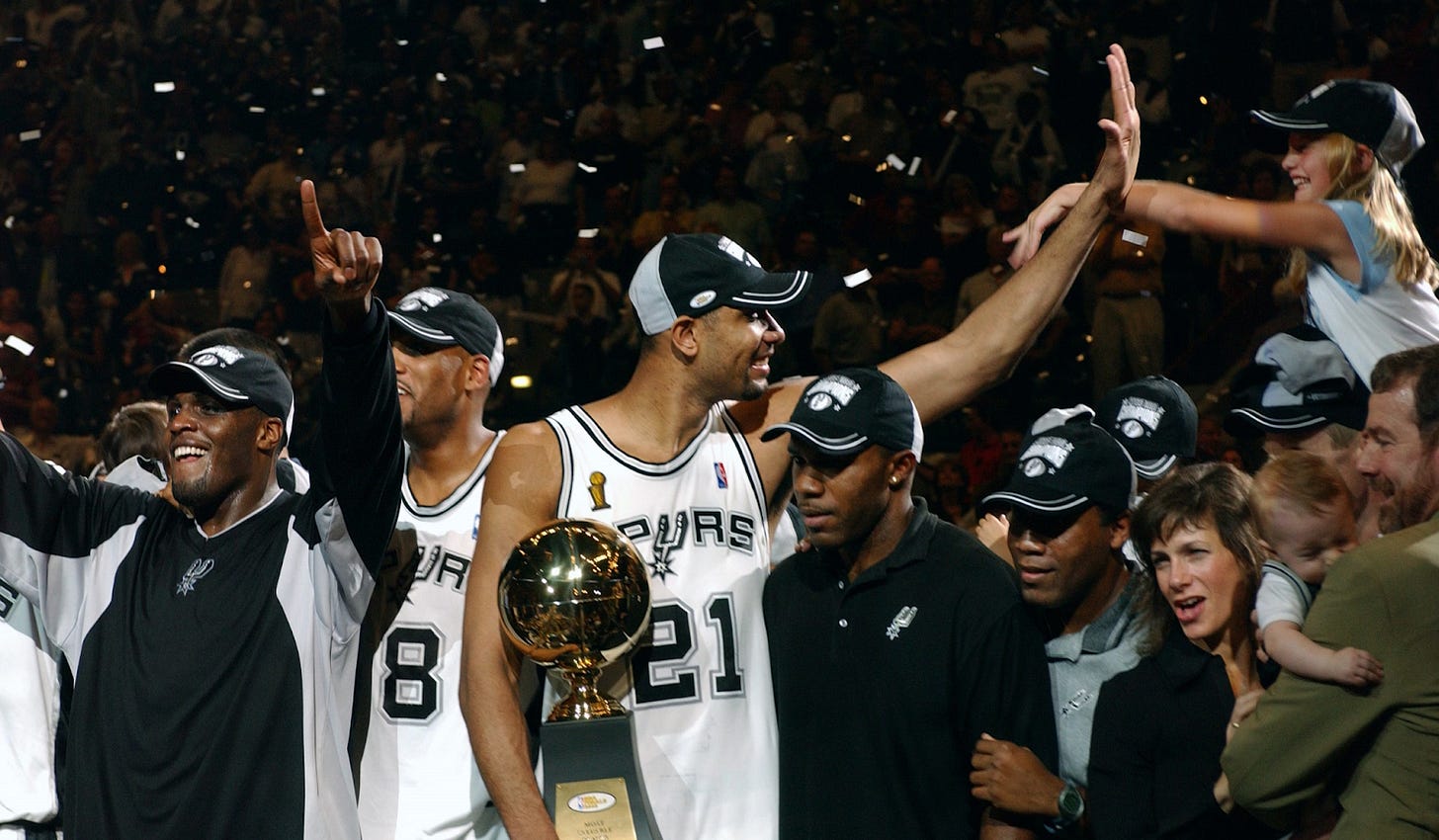

The San Antonio Spurs were nobody. Their black and white jerseys had as much color as a domino - a physical manifestation of the ego-less organizational structure. Every other contender had cocky superstars that led the charge like guerrilla generals. Tim Duncan barely spoke. He looked like a really nice guy. When the Spurs won championships, the world kept on moving; outside of San Antonio, no one cared. After winning his first MVP in 2002, Tim Duncan spun the block and won another MVP in 2003, this time beating Kevin Garnett and Kobe Bryant for the prize.

The Spurs would win a championship that same year after Tim Duncan’s all-time Game 6 performance:

21 points, 20 rebounds, 10 assists, 8 blocks

Spurs went on a 19-0 run to beat the New Jersey Nets

Tim Duncan was named Finals MVP

While Tim Duncan actively sidestepped the limelight, Coach Gregg Popovich embraced his role as face of the franchise.

Yes, the face of the franchise was a coach.

Media outlets from The New York Times to ESPN describe the Spurs as Popovich’s team, not Duncan’s. Why would they describe it as Duncan’s? He gave them no ammunition for their narratives, no ripe soundbites to squeeze juice out of. But Gregg Popovich was branded as a basketball savant who engineered championships using a squadron of silent soldiers - he was the masterful grandmaster and the players were black and white chess pieces. Popovich’s persona became more powerful every time he yelled at the referee, every time he benched his best players without probable cause, every time he gave a one word answer at the press conference.

If Union Square Ventures were an NBA team, they would be the San Antonio Spurs.

System driven.

Military level discipline.

Predictably patient.

Small market.

Longevity across cycles.

Brad Burnham is Tim Duncan. The intellectual heavyweight quietly responsible for putting points on the board. Brad came up with a sharp thesis from the fat slab of marble that is Internet investing, carving away until a beautiful conviction emerged from the blank canvas.

Fred Wilson is Coach Pop. Face of the team. When you hear Union Square Ventures, Fred Wilson is the image that flashes in your mind’s eye. His blog averaged 300,000 unique monthly visitors in the early 2010’s; every week Fred’s thoughts were read by enough people to fill the AT&T Center in San Antonio. He delivered clever musings, controversial takes, random thoughts, investment ideas. Fred Wilson’s AVC blog was the precursor for today’s media driven venture capital landscape.

Over time the USV team evolved.

The team stayed lean relative to fund size, but more partners joined the ranks, and a limited number of junior investors were welcomed in.

In 2011, Andy Weissman joined USV from Benchmark, he became an integral partner and still plays a large role in crafting investment theses.

In 2016, Albert Wenger was promoted to Managing Partner, joining Fred as head of the firm.

In 2017, Rebecca Kaden joined USV from Mavron.

Nick Grossman is the most recently promoted partner at USV - a former Stanford grad with experience in urban planning and running startup incubators.

Outside of the partners, USV generally employs 3-5 analysts and associates at any given point.

Over time, the USV thesis evolved with the market.

2012 (v1): USV invests in large networks of engaged users, differentiated through user experience, and defensible through network effects.

2015 (v2): As the market matures, USV looks for less obvious network effects, infrastructure for the new economy, and enablers of open decentralized data.

2018 (v3): USV backs trusted brands that broaden access to knowledge, capital, and well-being by leveraging networks, platforms, and protocols.

In 2021 USV raised a Climate Fund to invest in companies and projects that provide mitigation for or adaptation to climate change. While it’s still early, the Climate Fund has underperformed so far, with a measly 6% IRR.

For context, USV 2019 clocks in at a 34% IRR as of June 30, 2025, and USV 2016 is at 49%.

Let’s take a left turn and tell a cautionary tale about climate funds.

Kleiner Perkins was one of the most coveted venture capital brands for a long time, probably a more prestigious and storied shop than Sequoia.

For more than thirty years, the large partnership - formally known as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers - invested in the defining technology startups of the late 20th century. Sun Microsystems by Vinod Khosla, Netscape by Marc Andreessen, Amazon by Jeff Bezos, Google by Larry Page.

In 1986, Vinod Khosla joined the Kleiner Perkins team as a partner.

There were too many cooks in the Kleiner kitchen.

Mitch Kapor and Frank Caufield were the level headed managers. Tom Perkins was the ego-driven rainmaker with a temper. John Doerr and Vinod Khosla were the up-and-coming stars. Doug Mackenzie was the intellectually curious analytical mind that asked hard questions, a natural balance to the optimism other partners brought.

By the early 2000’s, Kleiner Perkins had ten general partners, a significantly higher number than comparable firms like Benchmark, where six general partners made decisions.

In 2004, Vinod Khosla was tired of the bureaucracy and left to start Khosla Ventures.

Doug Mackenzie and another Kleiner partner named Kevin Compton left to start Radar Partners that same year.

John Doerr inherited the KP throne and filled the partnership with loyal comrades from his inner circle.

This power transfer meant no one was there to challenge his judgement.

In 2006, John Doerr launched a climate fund at Kleiner Perkins to invest in technology that fought climate change. He increased exposure to “cleantech” in 2008, earmarking just under $1B to the sector. Doerr had a field day talking to the press about Kleiner Perkin’s environmentalist take on capitalism, dropping gems like “You remember the Internet? Well, I’ll tell you what. Green technologies - going green - is bigger than the Internet” and even quoting his teenage daughter, “Dad, your generation created this problem; you’d better fix it.”

The climate fund was the beginning of the end for Kleiner Perkins.

Twelve years after investing in the 2006 climate fund, one limited partner claimed that he lost nearly half his capital.

The 2008 climate fund fared better, with Beyond Meat producing solid returns alongside a few other names, and that vehicle ranked above average for its vintage year.

But Kleiner Perkins struggled to recover after fumbling its fortune on fairweather hopes; its partners started to drop from the Forbes Midas List like flies, and firms like a16z and Founders Fund began to gain traction with founders.

If the partners that left in 2004 - Khosla, Compton, Mackenzie - had stayed, the chances of Kleiner Perkins launching a climate fund would be near zero. Both Doug Mackenzie and Kevin Compton were openly critical of cleantech because it was capital intensive, slow to mature, and prone to changing regulation. Kevin Compton believed devoting sizable sleeves of capital to ending climate change would contradict the wisdom that Tom Perkins instilled in them as young investors. If anything, they should test the water by allocating small seed checks from the flagship vehicle before risking real bread. But alas, Doerr’s power was unchecked, and many limited partners who invested in 2004 were worse off. Perhaps there’s a convincing reason as to why now is the right time to invest in a climate fund. But there are structural issues that make that thesis challenging, such as macroeconomic risk, tension between mission impact and returns, as well as the sector’s capital intensive nature. It’s also fair to wonder if USV’s Climate Fund is a move away from what made them successful in the first place, sort of like KP’s move in 2004.

Union Square thesis updates generally drop every three years, and while it might not seem like a critical event to outsiders, the thesis drop is a cultural event for certain cadres of early stage investors.

The most interesting and relevant thesis tweak, in my humble opinion, quietly arrived on December 17, 2024.

In an article on the USV blog titled “Four Futures”, a team of analysts led by partners Rebecca Kaden and Nick Grossman described the firm’s approach to finding value in artificial intelligence companies. This thesis drop was both unorthodox and timely, as just a month later USV announced a new fund.

Four Futures describes four different scenarios that could play out as the business of artificial intelligence matures. The team of USV thinkers identified four different opportunities - fat models, defensible niche models, actually open AI, and network effect applications - that each landed somewhere on a two dimensional graph with fast / slow on the y-axis and closed / open on the x-axis.

Fat Models: in this future, the foundational AI models accrue nearly all the value, and the dominant players will be the small number of giant foundational models and the infrastructure they need to continue to effectively scale. USV’s investment strategy to plan for this future is to back companies that are building the infrastructure (energy, hardware, software) to enable the fat models. There will also be room for counterpositioned model architectures.

Defensible Niche Models: in this future, foundational AI acceleration slows, which makes room for smaller, niche models that can bridge the gaps in larger foundational models. Specialized models for biotech, defense, healthcare, will be important.

Actually Open AI: in this future, models advance both rapidly and openly, with many interdependent models accruing value and significantly increasing the size of the pie. My intuition is that this scenario is less likely relative to the others.

Network Effect Applications: in this future, the rate of progress in the foundation models slows down and the ecosystem is open. Models have gaps in their abilities and more specific scope, leaving room for startups to productize AI into applications that sit on top. This is the scenario a lot of startups and venture funds have been preparing for.

Frontier, or “fat”, models outside of the transformer architecture are perhaps the most interesting opportunity in this framework. Extraordinary amounts of capital have already been invested into the transformer architecture which powers large language giants like OpenAI, Anthropic, xAI, and the like. The entire artificial intelligence ecosystem is built around the transformer architecture, and for good reason: it enables large language models, video generation, and even pharmaceutical drug design. Transformers scale smoother than any other architecture explored thus far, so throwing more resources at it has generally meant better models up until now.

On the other hand, with every advantage comes disadvantage. Very few startups are focused on exploring the abyss that is alternative architecture. The current incumbent has multiple obvious areas for improvement: energy efficiency, getting past the data wall, eliminating hallucinations completely, and more impressive neural networks. This is where the white space is with foundational models.

The reason white space exists is because building an economically useful foundation model outside of the transformer architecture is a moonshot. You’re better off building a SpaceX competitor. Any startup that can reach escape velocity here, however, will unlock the returns that venture investors die for. A contrarian approach is extraordinarily valuable if it is right, and to the contrary, a consensus approach is only slightly valuable if right. In a future where current large language models represent the epitome of AI progress, the upside for today’s investors is still not venture scale. But, in the less likely future that a superior architecture, or even an architecture complementary to LLMs, will be discovered, the upside in such technology would be incredible for early stage investors.

Putting technical specifications aside, Union Square Ventures - Brad Burnham in particular - is looking for increased openness in artificial intelligence startups.

Is there a mechanism that we can envision that can’t be evil in AI? And what will that look like? It will have something to do with openness. It’s going to have something to do with access and an inability for a platform to do a rug pull on all the value adders on top of their platform.

Brad Burnham, The Slow Hunch, 2025

Power transitions leave sports teams in shambles.

They’re arguably worse in the business of investing.

Every great fund has a couple of key founding members that put their hearts into the business, and when they leave, nothing is the same.

Like Bridgewater with no Dalio.

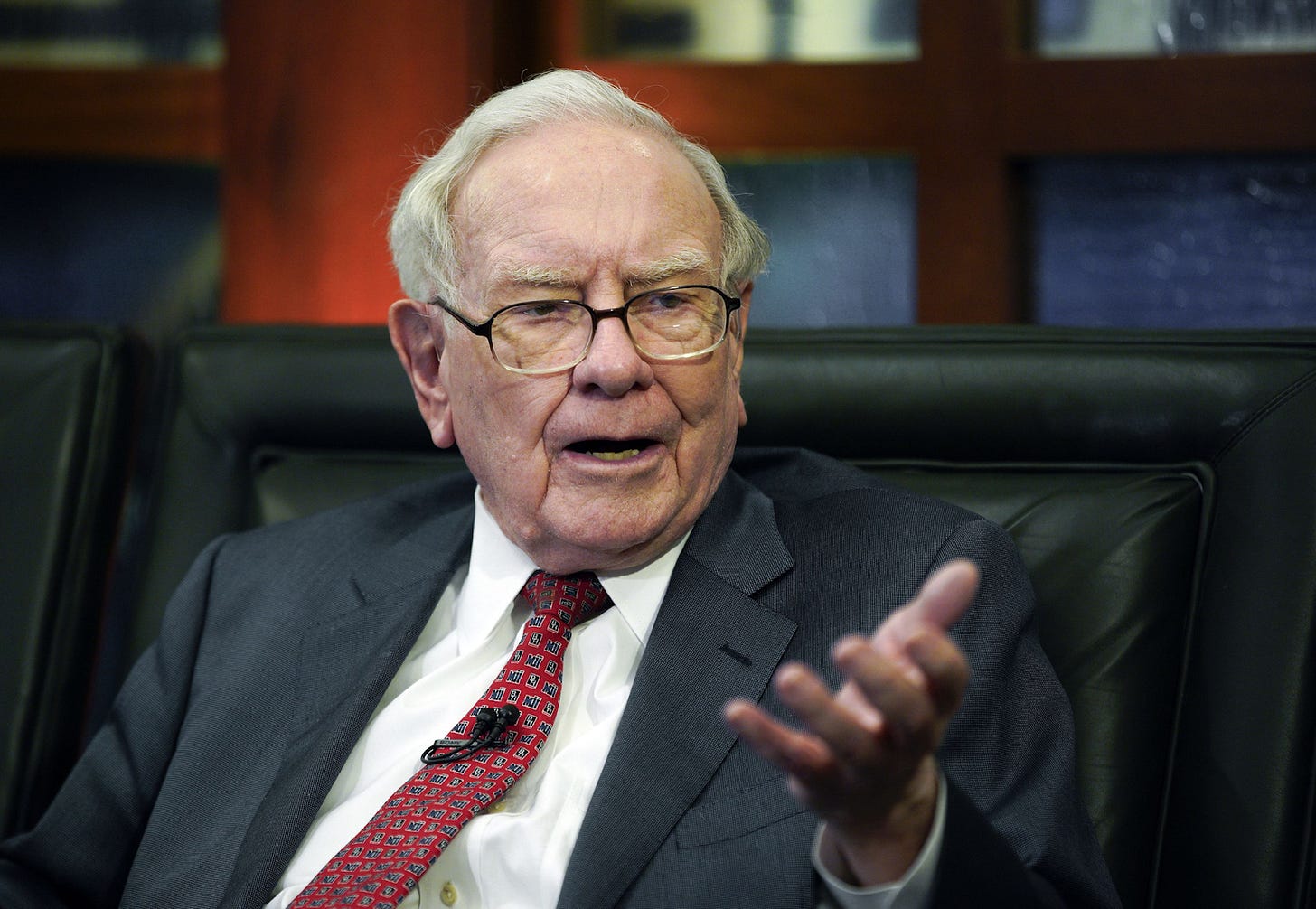

Like Berkshire with no Buffett.

Like Oaktree with no Marks.

Very few investing firms come out of a power transfer better than before.

When limited partners invest in a fund, they are investing in the judgement and execution abilities of the firm’s leading investors, as well as the culture those investors build. When the leading investor leaves, a lot of LPs follow. This rule mostly applies to hedge funds, venture funds, and boutique private equity shops, less so for the Blackstones of the world.

You can’t make a standard operating procedure to replace Dalio. Just like you can’t draw up a new playbook to make up for losing Lebron.

Union Square Ventures, at some point in the near future, will see Fred and Brad give the reins to younger partners.

Every party must end.

Over the course of two decades, Union Square Ventures changed the course of venture capital without raising a single billion dollar fund.

When USV 2004 was announced, venture capital in New York City was still a paradox.

Now, New York City is an established venture ecosystem, second only to the Bay Area.

Countless top notch venture funds have made the Big Apple their primary residence:

Josh Kushner and Thrive Capital. $16B AUM.

Josh Wolfe and Lux Capital. $5B AUM.

Ben Sun and Primary Venture Partners. $1B AUM.

The city received ~$29B in venture funding over the course of 2024, 13% of all venture funding in America.

And to think all of this might have not been possible if Kleiner Perkins was fine with accepting money from a public institution like UTIMCO…

This is the domino effect.

A small initial push will cause a larger object to fall, which, in turn, can knock down a larger object than itself, until seemingly immovable objects fall at the end of the chain. Once the first block falls, subsequent wins build on each other.

There are other theories that explain a similar occurrence, most notably the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect was conceptualized by Edward Norton Lorenz, a mathematician and meteorologist with degrees from Dartmouth, MIT, and Harvard. Lorenz came up with modern chaos theory, a branch of math devoted to explaining the behavior of dynamical systems. In 1969, he published a paper on the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect, by definition, is the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change to one part of a system can result in large differences in a later state. To hammer his point across, Lorenz used an example of a seagull flapping its wings, causing minor perturbations in the atmosphere, leading to a storm starting in another part of the country at a later time. Before publishing, Lorenz changed his example from a seagull causing a storm to a butterfly in Brazil causing a tornado in Texas, for the sake of delivering a more poetic visual. Lorenz’s intentions were to apply his mathematical background to meteorology in a way that hadn’t been done before, and he succeeded in a way that no one could have predicted. His findings transcended the confines of academia. The butterfly effect can be used to explain why the San Antonio Spurs won so many championships from 1999 to 2007, or why President George Bush got re-elected in 2004. Movie directors and songwriters alike used the name as a title for their projects. And at first glance, the butterfly effect might seem like the more applicable theory to explain the series of random events that took place after UTIMCO couldn’t get access to Kleiner Perkins, which led to the Union Square Ventures investment, which led to a series of successful funds, an unparalleled portfolio fund for UTIMCO, and the rise of NYC as a venture market. But life is not as random as we would like to believe. The butterfly effect is encoded with defeatist principles: a lack of agency, a system governed by chaos and unexplainable movements. The domino effect is a more accurate mental model because it requires and rewards positive activation energy - you must put your ego aside and push until the first domino falls.

If Fred Wilson gave up on investing after Flatiron, there would be no Union Square Ventures.

Keep pushing.

Appendix:

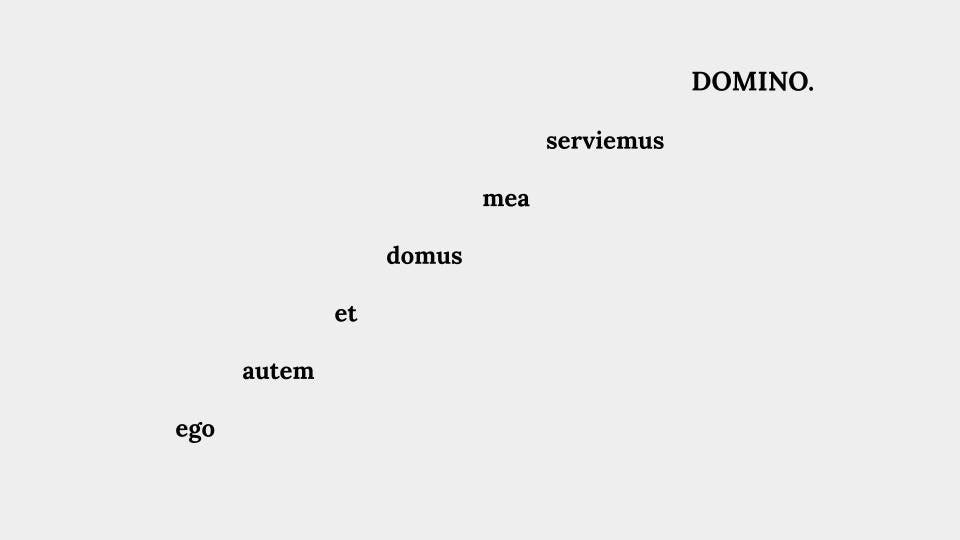

nunc ergo timete DOMINUM et servite ei perfecto corde atque verissimo et auferte deos quibus servierunt patres vestri in Mesopotamia et in Aegypto ac servite DOMINO.

sin autem malum vobis videtur ut DOMINO serviatis optio vobis datur eligite hodie quod placet cui potissimum servire debeatis utrum diis quibus servierunt patres vestri in Mesopotamia an diis Amorreorum in quorum terra habitatis.

ego autem et domus mea serviemus DOMINO.

Joshua 24:14-15

Now, therefore, fear the LORD and serve him completely and sincerely. Cast out the gods your ancestors served in Mesopotamia and in Egypt, and serve the LORD.

If it is displeasing to you to serve the LORD, choose today whom you will serve, the gods your ancestors served in Mesopotamia or the gods of the Amorites in whose country you are dwelling.

As for me and my household, we will serve the LORD.

Joshua 24:14-15

Oh my gosh! What a beautiful way to bring what’s happening in the investment world home to me, thus enabling me to be well educated, equipped and informed before making decisions. I couldn’t keep my phone down till I read the last word! God bless you Mainstreet media staff!