The USV Story: You Only Live Twice

If he dies he dies. Part Two featuring Fred Wilson, Brad Burnham, and Albert Wenger.

Previously:

In Ian Fleming’s novel, You Only Live Twice, James Bond pens a haiku that still holds weight today:

You only live twice

Once when you are born

And once when you look death in the face.

Fred Wilson died already.

Now he was ready to start his second life as a fund manager.

Union Square Ventures deployed capital at a snail’s pace during the first year of their investment period, making just four investments over the course of twelve months.

Consider the absolute inversion of pace relative to Fred’s previous fund: Flatiron made ~13 investments a year, minimum. USV was not being lackadaisical, rather, the two partners wanted to exercise extreme caution before jumping into the waters. Remember, Fred and Brad were investing in Internet applications just a few years after the dot-com bubble burst, and the taste of cash being lit on fire was still fresh on the tastebuds of investors everywhere. They knew that getting ahead of the curve was important, but they also knew that USV needed to select the right companies with surgical precision.

One of their first investments that year was Delicious.

Josh Schachter founded Delicious in 2003 and raised capital from Union Square Ventures in 2004.

Delicious allowed people to bookmark webpages to the cloud, and the most important thing about it was people would leave tags, and you could follow the tags and see all of the webpages there. It was a social company that combined the concepts of user generated content, webpage discovery, and cloud technology in a way that had not been done before. USV invested a small amount relative to total fund size, between $1M - $2M according to Fred Wilson’s interview with The Hunch.

Yahoo acquired Delicious less than a year after USV’s check, and the fund made $10M from the buyout, somewhere between a 5-10x return in a very short period, but not especially transformative to the aggregate pool of capital. The major win here was not the financial return, but the precedent that Delicious set. It validated the USV thesis of “Web 2.0”, or the social web, which is centered on the idea of open networks and using the Internet to connect with others in different places.

So Delicious is one of the four investments from that first year. It’s worth wondering out loud, if your full-time job is to make investments and you only make one every three months, what are you doing the whole time?

Fred was pissing off his limited partners.

He wouldn’t stop blogging.

“I was writing a blog and I could find something interesting to write about every single day. The dirty little secret about my blog is that many of the ideas on my blog were Brad’s ideas that he would come in and talk to me about for 15 or 20 minutes, then the next morning I would write a blog post and take full credit for these ideas.”

Fred Wilson

“I remember having conversations with our limited partners where they were saying, ‘does Fred actually do any work?’ Because he was writing. That was a brand new idea. Limited partners were saying you are spending all of your time writing, giving away all of your best ideas, this makes absolutely no sense to us, how could this work? Yet, we both intuitively believed in it, and it turned out to be the first real blog in the VC industry…”

Brad Burnham

Writing helped Fred and Brad (a) understand social networks much better (b) attract forward thinking founders and investors to USV and (c) stay busy during down periods.

Warren Buffett talks about this a lot - the best investors are the most patient ones, the ones willing to do nothing when nothing should be done. To the contrary, there are a lot of very good investors who are locked out from being great because they force action when the market is calling for temperance. This is why Buffett also believes the best investors read and write nonstop, busying themselves with learning and setting themselves in position to strike when the time is right. Buffett reads books, financial reports, and newspapers for five hours each day, allegedly.

Another early USV investment was FeedBurner.

FeedBurner was founded in 2004 by Dick Costolo and some of his fellow consultants at Andersen Consulting, which eventually became a part of Accenture, the $150B consulting giant.

Unlike the other portfolio companies, FeedBurner was one of the few Internet infrastructure plays, as opposed to Internet application plays.

The company was a RSS feed management service that monetized RSS feeds by inserting targeted ads.

RSS = “really simple syndication”, infrastructure that allows content from websites to be automatically syndicated to other sites or subscribers, eliminating the need to constantly check a particular site

Feedburner provided analytics for smaller publishers and podcasters that did not have access to proper engagement data

The company also monetized RSS feeds by inserting ads and then distributing a portion of proceeds to the publishers/podcasters

Fred led the Series A investment in 2004 primarily because he was a passionate user of the company and understood the value proposition thoroughly. Analytics for publishers was a very important hook to get customers in the door - Fred wrote on his blog “I am trying out this new RSS enhancement service called FeedBurner… It’s going to allow me to get to see statistics on the people who read my RSS feed, what they read, etc. This is something i’ve wanted to see for a while now”.

By 2006, FeedBurner was the infrastructure behind feeds from The New York Times, TechCrunch, and the BBC.

Google acquired FeedBurner in 2007 for $100M.

That same year, Fred closed a deal that would change his life forever.

Fred was in San Francisco meeting with a founder in a co-working space. What the founder was working on isn’t important, what was important is that at some point during their conversation, the founder said, “This Twitter thing is really interesting.” That was enough evidence for Fred to dig deeper.

He reached out to Evan Williams, Twitter’s co-founder.

FRED: I’m in San Francisco. I hear you’re thinking about spinning Twitter out of Odeo. We’d love to finance that spin-out. Can we talk about that?

EVAN: Why don’t you come back in a few weeks and meet with Jack and I… We’ll talk more about it.

You probably feel like you just walked into a movie theater late and missed critical context… What is Odeo?

Evan Williams created the blog.

Not literally, but he helped popularize the term as the founder of a startup called Pyra Labs in 1999. At Pyra, their most notable product was called Blogger, a web app for creating blogs that caught on like wildfire. Google acquired the company in 2003, and Evan Williams, after a number of failed side projects, became a young prodigy in Silicon Valley. The downside of the acquisition was that Evan no longer had the creative freedom he valued so highly… he would only last at Google for so long.

Each day on the way to Google’s office in Mountain View, Evan would turn on some music to kill time. What he really longed for, though, was the ability to listen to a good podcast, a more productive use of downtime than listening to the same songs over and over. Odeo would allow users to do just that - it was a website directory for podcast discovery.

Fun Fact: Instagram founder Kevin Systrom was an intern at Odeo during the summer of 2005.

In 2004, Evan founded - and funded - Odeo alongside former employee Biz Stone.

In 2005, Apple launched iTunes 4.9 which supported podcasts.

Odeo was dead on arrival.

Evan Williams told his crew to come up with a new idea so that they could pivot Odeo into a sustainable business. Jack Dorsey, Noah Glass, Biz Stone were the main guys on a fairly small team of founders and engineers.

Jack Dorsey and Noah Glass started obsessing over an idea to give real time status updates in a social network setting, a problem each of the builders claimed they had independently been working on for a long time. Biz and Evan were relatively skeptical about the potential for this new type of social network to gain traction, but Evan told Biz to help Jack and Noah build it out nonetheless.

A year later, mid-2006, Evan told his investors about Twitter and started having conversations about buying the company back from them in a spin-out.

This is when Fred sent Evan those messages.

A few weeks later, Fred and Brad flew out to SF to meet Evan and Jack.

“What was so interesting about that is they interviewed us. We never got a pitch from them. We went in saying, ‘We like this, we want to invest in it.’ We didn’t commit to investing, but we gave them the sense that we would. So they spent the hour, hour and a half, really digging into what we thought they should do in terms of go-to-market. How they should bring Twitter to the world.”

Fred Wilson

USV’s go-to-market strategy for Twitter was stupid simple: keep all interactions on the Twitter platform, let other people build on the platform openly, focus on social and the web.

In hindsight, this approach seems obvious - but every other venture capitalist Twitter talked to was telling them to go-to-market with mobile phone carriers and make the core interaction text message based. On top of that, the consensus among other venture investors was to monetize the minutes put on texting networks. Fred and Brad were vehemently against this; their experiences funding social internet companies over the past decade gave USV conviction that monetizing the interaction component - the act of tweeting - would disincentivize users and prevent network effects from developing properly.

USV’s plan stuck out like a sore thumb.

Evan gave Fred a call and told him that he liked their plan for Twitter, then asked him to finalize an investment amount and valuation price.

Union Square Ventures would go on to co-lead Twitter’s $5M Series A in 2007, investing $2.5M alongside Spark Capital.

This one investment put Union Square Ventures on the map forever.

Twitter would IPO in 2013, just six years after the Series A, at an $18B valuation.

This was Fred and Brad’s defining career win - a decacorn IPO at a time when decacorns were an even rarer occurrence than they are today.

At IPO, USV’s stake was worth ~$700M+, a ~300x+ return in just six years.

If Twitter was the only investment in Fund I that returned capital, Fund I would still be a top 1% fund within the 2004 vintage cohort.

But USV had other home runs in the bag:

Twitter: $18B IPO (Series A lead)

Zynga: $7B IPO (Seed investment)

Etsy: $3.5B IPO (Series A lead)

Tumblr: $1.1B acquisition (Seed investment)

Indeed: $1B acquisition (Seed investment)

5 of the 20 investments Fred and Brad made were unicorns, and all five of those investments returned capital in the form of an acquisition or IPO. Phenomenal.

Union Square Ventures 2004 was one of the greatest venture funds of the 2000 - 2010 period.

The cash on cash return was 13.8x with a 66% IRR.

UTIMCO invested $22.2M and received $307.4M back

Generational performances open doors to generational payouts.

Fred and Brad could have gone to their limited partners after these early wins and loaded the Brinks truck with half a billion dollars or more. Venture capital is a business, and managers must choose a business model. Some fund managers walk a tightrope optimizing for both management fees and returns, while other managers prioritize one and neglect the other. Certain firms aim to raise as many billion dollar funds as possible, drown the market with capital, and expand across all sectors, stages, and geographies. Yet others restrict fund sizes with rigorous discipline, focus on thesis driven investing, and pride themselves on performance alone. The casual observer might assume the differences between these two types of investors comes down to internal decision making frameworks constructed by consultants from ivory towers. But the differences between these two managers - the hyperscaler and the boutique investor - cannot be explained away by differences in high level strategy or mental models, rather, these managers are products of different environments. They grew up investing at different times and experienced fundamentally different markets which shaped their philosophies.

Generational trauma is the difference between the hyperscaler and the boutique investor.

In 2011, economists Ulrike Malmendier and Stefan Nagel wrote a research paper titled “Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk Taking?”. The article investigates whether individual experiences of macroeconomic shocks affect financial risk-taking across generations. Malmendier and Nagel use data from the Survey of Consumer Finance (1960 - 2007) and find that individuals who have experienced lower stock returns throughout their lives are less likely to take financial risks, invest a lower percentage of their savings in stocks, et cetera. This general trend holds true for other asset classes like bonds. To the contrary, those who have experienced greater returns are much more likely to invest a higher percentage of savings, and this effect is particularly true for younger people. If you happened to grow up when inflation was high, you invested less of your money in bonds later in life compared to those who grew up when inflation was low. If you happened to grow up when the stock market was doing well, you invested more of your money in stocks later in life compared to those who grew up when stocks were weak. Where and when you were born has a much greater impact on how you approach financial risk than most people realize.

Fred and Brad were survivors of the dot-com bust.

Their experiences of seeing one of the largest American investment bubbles inflate then collapse impacted the way they approached fund size, forever. To this day, USV caps its core fund vehicle at $275M while other firms raise billions at once.

But Union Square Ventures is not an anomaly - venture firms founded between 2000 to 2005 by venture investors who lived through the dot-com bust almost all remained boutiques.

First Round Capital, True Ventures, Floodgate. All of these firms focused on early stage investing, specific sectors, and remained small relative to their peers.

During the 2005 to 2010 period, investors that were founders during the dot-com bubble built platforms that would become some of the better known megafunds today - Founders Fund was launched late in 2005, a16z was launched in 2009.

The correlation is far from perfect and the sample size is rather small but an interesting hypothesis nonetheless. Would Fred and Brad have been hyperscaler fund managers if they were born ten years later? Or maybe if they were founders during the dot-com era like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen?

Albert Wenger was a founder during the dot-com era.

Well, sort of.

He was doing a PhD at MIT during the mid 1990’s and decided to launch a company with two of his professors. Things fell apart, but Wenger got his feet wet in the business of technology and quickly realized that he would rather invest than operate. Wenger was based in New York City and mingled in the same venture-startup social circles that Brad Burnham occupied.

As Brad was leaving AT&T Ventures, Wenger was advising and investing in startups based in NYC. The two had built a strong relationship by this point, and they started having conversations about launching a venture fund together.

This was before Brad reconnected with Fred.

In an alternative universe, Albert Wenger and Brad Burnham successfully launch a venture fund in 2001/2002 and Union Square Ventures doesn’t exist… Imagine that. Luckily, not a single limited partner wanted to back an emerging manager that quickly after the dot com crash.

“Brad and I tried to raise a fund in the nuclear winter after the implosion of the dot-com bubble.”

Albert Wenger

After the unsuccessful attempt, Wenger stayed close to Brad, and after Brad launched USV, Wenger ended up working for one of their first portfolio companies, Delicious, as an executive. When Delicious sold to Yahoo, he got even closer to the guys, spending his days lounging at USV headquarters, bouncing ideas off Fred.

Things ultimately came full circle when Union Square Ventures brought on Albert Wenger as a partner in 2008.

That same year, Union Square Ventures dropped their second flagship fund, Union Square Ventures 2008. Thesis wise, USV was targeting the same opportunities that made their first fund extraordinarily successful - Internet based networks like Twitter and Tumblr. The macroeconomic environment, however, was much different. 2004 was post-dot-com recovery time, an opportunistic window of time during which the bleeding was over but limited partners were still scared to come outside. It was an ideal time to start a venture fund if you could. The macro tailwinds combined with a well positioned thesis, smart and connected investors, and exceptional discipline came together in a recipe for unparalleled DPI. 2008 was much different. Fred and Brad were still Fred and Brad, the thesis was still relevant, but now the focus was specifically on mobile apps and social media apps - the iPhone was a major platform shift USV wanted to build on. Also, in 2008 the global financial crisis was taking place in real time.

Union Square Ventures 2008 raised $156M, a 25% increase from USV 2004.

From this sophomore season vehicle, the guys would back some of the most culturally significant networks from the 2010’s: Foursquare (location), SoundCloud (music), and Stack Overflow (developers). USV’s reputation in the market was second-to-none for founders building network based businesses online, and their ability to sift through thousands of pitches to find the one diamond in the rough was best in class.

All of those investments combined don’t stack up to the fund’s top performer.

This one investment generated more than a third of the fund’s returns.

And it was sourced by the new guy.

When Wenger was studying at MIT, his PhD coursework centered on computer science research; his technical sensibilities were lightyears ahead of Fred Wilson and Brad Burnham, not that it matters in isolation, but in this particular situation, it matters a lot. The story starts with a man named Dwight Merriman. Dwight was formerly the founder of DoubleClick, a standout adtech startup that took New York by storm. He was launching a new company called 10gen with the goal of pioneering “platform-as-a-service”, meaning infrastructure for software developers to build on top of without worrying about storage, middleware, APIs, etc. 10gen was going to make building Web applications 10x easier than before. As someone skilled in the software development game, Wenger saw the vision and immediately hopped onboard with a $1.5M check.

10gen ran into several critical problems early on in development.

Developers weren’t ready for technology this advanced. Most software engineers were still learning the fundamentals of cloud hosting. For context, Amazon had just launched its first cloud hosting product - EC2 - and adoption was in the first inning. To add another level of complexity, 10gen’s ambitious vision meant building three different things at once: a distributed application runtime, an orchestration system, and a new database. The team was spread impossibly thin, which delayed progress significantly.

The one thing that did work was their internal database.

10gen ran several demos for outside developers to generate customer interest in their platform-as-a-service product.

Every demo had the same response: we’re not interested in the product right now, but can we use your database?

Developers loved the database scalability and coding friendly API - in a matter of fact, they had never seen anything like it. 10gen’s internal database was able to store humongous amounts of data efficiently, and after a few revealing demos, the team decided to pivot.

10gen became MongoDB, a shorthand version of “Humongous Database”.

MongoDB became a $1.6B company in 2014, eventually going public in 2017.

Albert Wenger hit a homer.

“If you look at the portfolio Albert’s built since 2008 when he joined us from Delicious, he’s made 15–20 investments. I think at least half of them could be billion-dollar companies… He’s probably the best relatively new VC in New York City based on his track record. There are other people you mentioned — Josh Kushner, Dave Tisch and Mike Brown — who could emerge as good or better than Albert, but they haven’t been at it quite as long… (Albert flies under the radar) because I have such a big profile and it’s difficult to have multiple front people in a venture firm.”

Fred Wilson, 2014 interview.

Like Kawhi Leonard on the San Antonio Spurs, Wenger stood out at Union Square Ventures.

Kawhi Leonard was a kid from Compton who joined a basketball dynasty largely built on the backs of foreign players like Tim Duncan (Virgin Islands), Tony Parker (France), and Manu Ginobili (Argentina). The Spurs dynasty already experienced success before Kawhi arrived. Tim Duncan and Coach Pop won championships in 1999, 2003, 2005, and 2007. By 2014, Duncan, Parker, and Ginobili were on their last legs. To make matters worse, the Spurs were lined up against a three headed behemoth known as the Miami Heat, featuring the best player in the league, Lebron James. Kawhi Leonard wasn’t meant to be a superstar - he was a 15th pick traded from the Pacers to the Spurs. He also didn’t match the team’s culture. But he was by far the best defender on an aging team, gifted with outlandishly long arms and quick feet. In 2014, he was the young spark that lit a fire in San Antonio, winning a championship and a Finals MVP in the process.

Like Kawhi, Wenger joined a team that already had its fair share of blockbuster wins: Twitter, Tumblr, Etsy, Zynga. He also didn’t fit the culture in any way. A German immigrant, he still had a slight accent that marked him as an outsider relative to Fred and Brad. His technical prowess also made him a bit of a nerd. Fred and Brad were both lifelong investors who didn’t tinker with code. With every disadvantage comes advantage, however, and Wenger’s oddities allowed him to source Fund 2’s biggest winner in MongoDB. MongoDB aged like fine wine; the stock is currently up 970%+ since IPO, with a market cap of ~$27B.

Despite some strong outcomes, Union Square Ventures 2008 took a long time to be realized and ended up with very solid performance but came nowhere near Union Square Ventures 2004.

Union Square Ventures 2008:

4.1x cash on cash return

21% IRR

UTIMCO invested $23.7M and received $97.2M back

Change happens slowly in the moment, and it can only be truly appreciated in hindsight.

In 2011, Facebook’s market cap was $50B.

Union Square Ventures did not invest in Facebook, which is a story for tomorrow, but Facebook’s growth from a college campus sensation to an S&P 500 company made the raw size of USV’s thesis crystal clear to investors. Social media was now big business, and no one understood it better than Fred Wilson and Brad Burnham. And if no one understood it better, then why not raise more money to capitalize on the opportunity at hand? When USV started up, a $125M fund was more than enough given the opportunity set; the market cap of the entire social media sector was no more than $100M. But now, things were changing - Facebook was worth $50B, Twitter was worth $8B, Tumblr was approaching $1B.

On January 15th, 2011, USV raised a $125M Opportunity Fund to invest in (a) USV’s most successful existing portfolio companies, (b) successful network based businesses that were initially funded by others, (c) special situations like a network spin-out, and (d) attractive opportunities in the broader market. The fund could theoretically write checks as small as $250,000 and as large as $25M.

A year later in January 2012, USV raised $200M for their third flagship, Union Square Ventures 2012.

USV 2012 quietly tip-toed away from broad social media platforms and waltzed towards vertical networks with clear value disruption.

Fintech: Coinbase, Carta

Education: Duolingo, Clever, Edmodo

Marketplaces: Kickstarter, Shippo

Coinbase, the cryptocurrency platform, carried the fund to unexplainable heights.

After an IPO in 2021, Coinbase’s market cap was $86B.

USV generated ~700x returns as a seed investor - their greatest investment ever.

I know I said USV 2004 was one of the best venture funds of its time.

But USV 2012 made 2004 look like a down year.

Union Square Ventures 2012:

22.8x cash on cash return

53% IRR

UTIMCO invested $25.9M and received $592.7M back

USV’s investment in Coinbase is a perfect example of the power law in action.

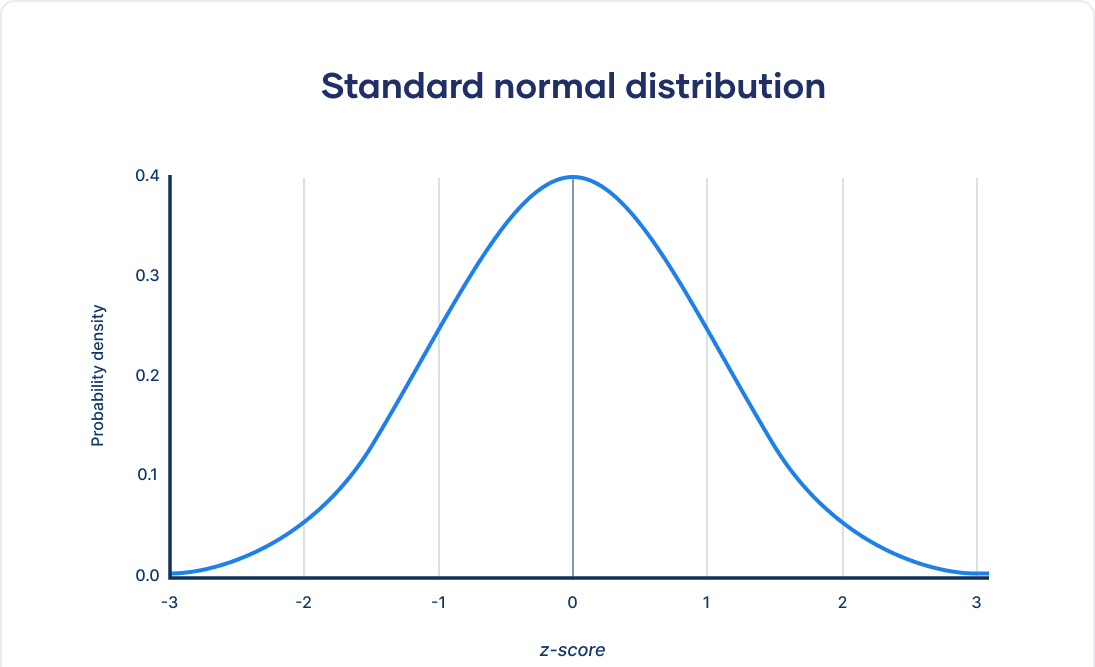

In a normal distribution, outcomes cluster around the mean. Take height, for instance. The average American man is around five foot nine depending on who you ask, and ~67% of American men fall within three inches of that average, call it 5’6 to 6’0. When you plot height on the x-axis and the probability that an American man will have that height on a y-axis, you will get a bell curve, or normal distribution similar to the picture below.

In a normal distribution, you can remove the biggest outlier from the dataset without meaningfully disturbing the average. So in a room of 50 American men, Victor Wembanyama can walk out and the average would still be around 5’9 - 5’10.

The power law distribution is skewed to the right. Instead of height, we can look to NBA draft picks. Every draft has sixty picks, from which roughly 1 MVP and no more than a handful of all stars will emerge. Roughly 20% of draft picks will make 80% of each draft class’s total earnings. Earnings are an imperfect proxy for success; the point here is that a very small number of NBA picks each year will go on to dominate production, become all-stars, and win MVP awards. If you are an NBA general manager, it is your job to draft a perennial all star like Shai Gilgeous Alexander over other prospects that appear more tantalizing in the moment. Remove SGA and Luka Doncic from the 2018 NBA Draft Class and you have one of the weakest draft classes of the past two decades. Total production plummets. This is the power law - a game’s largest winners account for the majority of wealth, production, points, et cetera. Venture capital is a game governed by the power law, and USV’s Coinbase investment is just one of many examples of this phenomenon in action.

Union Square Ventures’ consistency almost defies the power law in a sense; if you remove Twitter and Coinbase, their most valuable decacorn hits, all of their funds remain comfortably top quartile. Zynga, MongoDB, Tumblr, Duolingo, Carta, Etsy, Indeed, Kickstarter. Their roster of unicorn companies relative to fund size is first class; these guys are just good at venture capital, even if you account for luck. Now, in reality, USV is still obedient to the power law - Twitter elevates the 2004 fund from great to generational, and Coinbase takes the 2012 fund returns from tremendous to Thanos level.

The investors who provide venture capital funds with capital - limited partners - are playing a slightly different game. Their motivation first and foremost is to keep their job at their respective endowments, asset management funds, or pensions. Which reduces their risk tolerance. A famous saying among professional allocators sums it up well: no one ever got fired from investing in Sequoia.

At the end of last week’s memo, Lindel Eakman from UTIMCO (University of Texas endowment) admitted that their endowment only invested in Union Square Ventures because they couldn’t get access to Kleiner Perkins or Sequoia, the blue chip funds.

Over the course of two decades, UTIMCO invested $129M in Union Square Ventures and received $1.2B in cash back, a 9.3x cash on cash return and 59% IRR.

USV is, by far, UTIMCO’s best investment to date.

Twice is the only way to live.