The USV Story: Days Before Union

You've probably never heard of Flatiron Partners. The prequel to Union Square Ventures.

The USV Story is a three part series covering the history, strategy, and personalities behind one of the best performing venture capital firms in the world.

This is the deepest dive available on Union Square Ventures, brought to you by mainstreet media.

If you look up Flatiron Partners on Google, the first site that pops up is Flatiron Search Partners, a boutique executive search firm that does talent placement for consumer brands like Eight Sleep, Figs, and Planet Fitness.

This wasn’t always the case.

For about ten years, Fred Wilson worked at Euclid Partners, a New York City based venture capital fund.

Funny story on how he got there.

While studying Mechanical Engineering at MIT, he met his wife. His wife was going to New York City after graduation to work in fashion, so he followed her there and got a software job that lasted two years. It was during this time that he figured out New York was a city where the “money guys” ran everything. He figured if he was already working in technology, he should find a way to invest in it. So Fred starts reading up on venture capital and knocking on any door he could find. The response was the same everywhere: get your MBA and we’ll talk.

So Fred gets a Wharton MBA and applies to a firm called Euclid, starts as an associate, and eventually reaches the esteemed title of General Partner. Euclid was not a top venture capital firm by any stretch of the imagination, but it was a solid launching pad that Wilson would use to catapult his career in technology investing.

At the time, investing in Internet businesses was not popular.

Fred knew Internet companies would become the future, and Euclid was preventing him from fully exploring this promising opportunity set. He decided to part ways with the firm in the mid 1990’s.

Jerry Colonna was a journalist that landed a job at CMG@Ventures, an early stage venture capital fund. The New York venture capital scene was very small and tight knit, so Jerry had bumped into Fred early on, and the two shared the same thesis.

The Internet was going to change everything.

So when Fred was contemplating jumping out, Jerry answered the phone. Both men left the sedating comfort of an established fund and formed Flatiron Partners.

The name was a reference to their city - the Flatiron Building in New York is an iconic landmark specific to the Big Apple. Keep in mind, the New York venture capital scene of 1995 was not the New York venture capital scene of today. Silicon Valley was the undisputed headquarters of startup building, the capital for venture capital if you will, while New York City was a financial hub for investment bankers, the guys who wear suits and obsess over discounted cash flow models. Flatiron Partners was a very intentional name Fred and Jerry used to let the venture market know that New York was here now.

You can’t ignore us anymore.

Fun Fact: The Flatiron Building was auctioned off for $190M in 2023, but the winning bid failed to fulfill the terms of the sale. A second auction was held and the building was sold for $161M.

Flatiron Partners had a $150M target fund size, enough to buy its namesake skyscraper.

The thesis revolved around three key points:

Sector: The Internet was going to be huge and backing early stage companies in this sector would translate to outsized returns

Geography: New York startups were undervalued compared to Silicon Valley, which meant there was opportunity for geographic arbitrage.

Team: Fred brought venture dealmaking chops while Jerry brought media relationships to drive awareness of portfolio companies

While many legendary investors often struggle for years while raising their first fund, Fred and Jerry had no issue attracting capital for this extremely well timed thesis.

At the end of the day, venture capital - and institutional investing more broadly - is a business. You have founders, products, and product-market-fit, just like startup businesses do.

Fred’s first Flatiron fund pitch was a fantastic example of product-market-fit. Institutional investors immediately understood the unique value proposition and lined up at the door to foot the bill.

Chase Capital Partners and SoftBank were the sole investors for Flatiron Partners Fund I. Chase Capital Partners was the private equity arm of Chase Manhattan.

As Flatiron went to market with enough ammo to fund every founder in the city, the dot-com era began to take shape. Other investors started to take notice of the potential hidden in “Internet companies” around the same time. Amazon went public in 1997, eBay went public in 1998, and NVIDIA went public in 1999. A company known as theGlobe.com went public in 1998 at $9 per share and saw its stock skyrocket 600%+ on the first day of trading. Venture capitalists were convinced that if they could grab hold of an Internet company with the right team, an IPO could be expected relatively soon, which would lead to large payouts for investors. Founders saw where the venture capital money was going and made the rational decision to build Internet businesses in order to capture a piece of the pie. The market was so hot that some companies were commanding billion dollar valuations with no revenue.

Venture Capital Funding by Year:

1990: $3B

1994: $7B

1998: $28B

2000: $105B

This is the market that Flatiron was buying in.

From 1995 to 1999, Flatiron made 55 investments in Internet startups, most of which were based on the east coast to capture the geo-arbitrage their thesis outlined.

GeoCities:

Founded in 1994 by David Bohnett and John Rezner, GeoCities was originally called Beverly Hills Internet before making the name switch in 1995.

GeoCities was a social network that allowed users to create their own personal webpages for free and then grouped personal webpages into themed neighborhoods based on user location. For instance, a Hollywood agent’s personal page would be organized into the “Hollywood” section of the site.

GeoCities was far ahead of its time, forming the precedent for future social media giants like MySpace, Facebook, Instagram, etc.

From 1996 to 1997, GeoCities grew from 30,000 users to 500,000 users and scored a ~$9M Series A round from Flatiron in the process.

By 1998, GeoCities was one of the most visited sites globally, alongside Yahoo, MSN, and AOL.

Alacra:

Founded in 1996 by Steve Goldstein and Michael Angle, Alacra aggregated data sources for white collar professionals under one interface. It was one of Flatiron’s few B2B investments in the portfolio.

Finance, consulting, and legal workers could get a variety of paid subscriptions like LexisNexis and Factiva for one price and in one place.

Flatiron Partners led the Series A round and Alacra managed to scale to 500 institutional clients in the late 90’s.

TheStreet.com

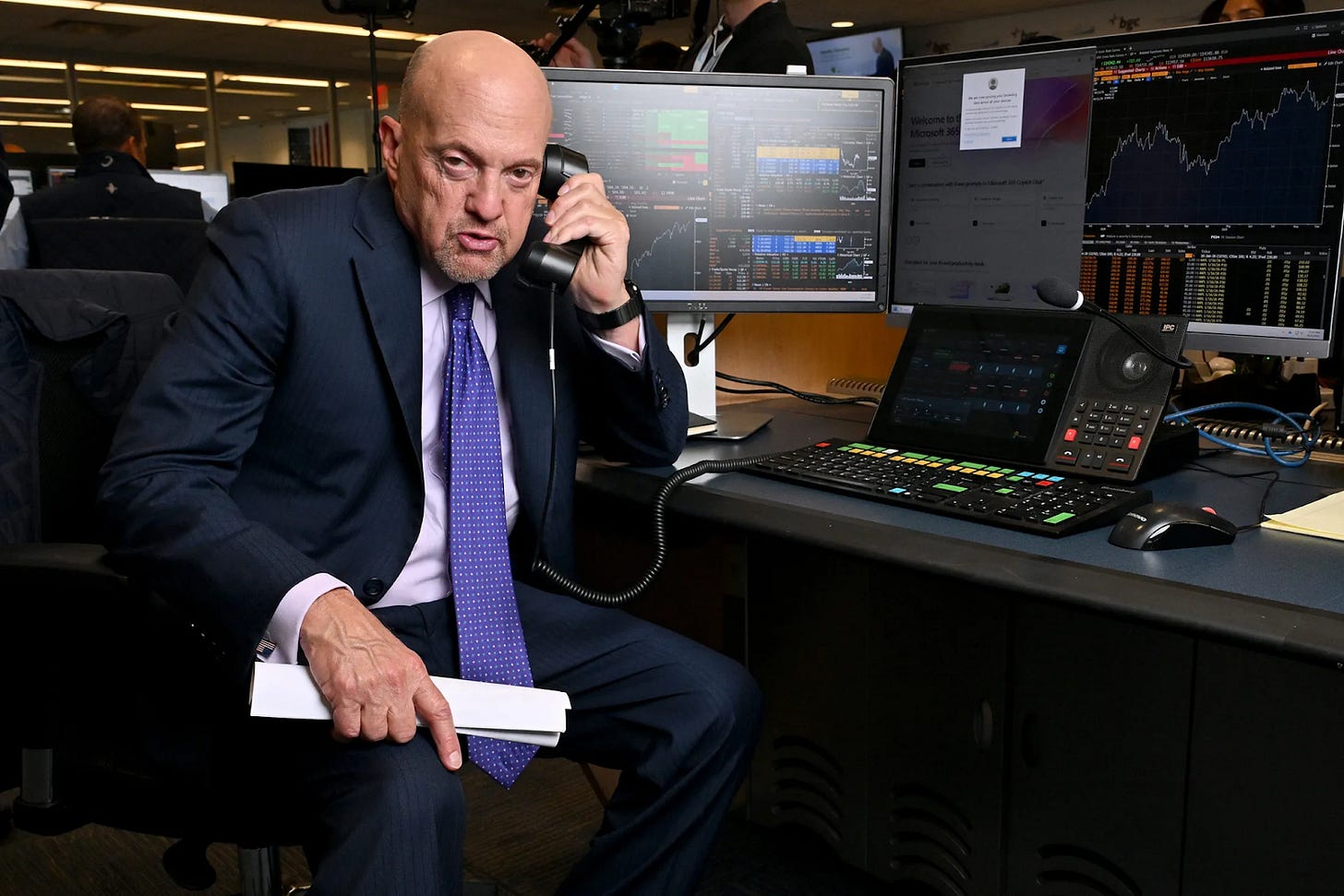

Founded in 1996 by Jim Cramer and Martin Peretz, TheStreet.com provided premium financial news and analysis online, and monetized using paid subscriptions.

TheStreet scaled to 200,000+ paid subscribers and developed first class brand credibility within the broader finance community.

Flatiron came in for an early $2M+ check in 1997.

“We made a lot of money… One time, on paper, I was worth as much in 1999, in 2000, as I am now. The difference is back then it was on paper.”

Fred Wilson

You can probably guess how this story ends.

But before we get to the bad part, let’s talk about the wins.

GeoCities ended up being one of the strongest outcomes from the Flatiron portfolio on multiple levels. In 1998, GeoCities went public at a $340M valuation, giving the Flatiron a very fast 10x+ exit. Just a year later, Yahoo acquired GeoCities for $3.57B in stock. A very, very, huge win financially. In an interview with Sarah Lacy, Fred Wilson said, “In 1999, we sold GeoCities to Yahoo, and I had all this high priced Yahoo stock… My wife said, ‘Let’s buy a townhouse in New York City.’ We sold enough Yahoo stock to buy the townhouse in New York City and renovated. A year later that was our entire net worth because everything else went to zero.” The GeoCities win is somewhat ironic given it was one of the only west coast based companies in their portfolio. This taught Wilson a critical lesson on thesis based investing - every fund manager’s mandate must be broken at some point.

The financial implications of GeoCities were extraordinary, but perhaps the more lasting victory is that the company was so far ahead of its time that it opened Wilson’s eyes to how lucrative social networks could be when combined with a platform shift.

Platform shifts = the Internet, the cell phone, etc.; game changing technologies that completely transform how people are communicating.

Another successful company Flatiron backed was TheStreet, which IPO’d in 1999 at a $1B+ valuation. TheStreet co-founder Jim Cramer would go on to become one of the most famous television personalities in finance, known for his hot takes that age like raw filet mignon left outside on a summer day.

“Everybody got caught up in the fact that, ‘Hey, we put $1 in today, and we took $10 out a year later. Boy, let’s do that again.’

That’s what happens in these kinds of situations is that everybody’s making money, and so more and more people want to get in the game. You want to keep doing it. I was certainly cognizant of the fact that at some point this whole thing was going to end badly.

We were selling companies as fast as we possibly could. In 1999, we had 55 investments in the history of Flatiron Partners, which was the first firm I started. I think in ’99, we sold 12 of them. We were trying to sell them as fast as we could. Then we turned around and kept making new investments. We took a lot of money out.

Then when the music stopped, it’s like a game of musical chairs. Then we realized, ‘Oh shoot, we’re not sitting.’ That’s when it got pretty ugly pretty quick.”

Fred Wilson

This is the bad part.

The dot-com bubble burst and wealth evaporated in real time.

Flatiron Partners began to lose money, most notably on a portfolio company called Kosmo that was essentially Instacart before Instacart. Kosmo delivered snacks, drinks, DVDs, magazines, and other small purchases to consumers in under an hour with no delivery fee. The company made money from marking up the products they were delivering and they also inked some wholesale business partnerships that brought revenue in the door. The growth was rapid: 1M customers, 15 cities, 3,000+ employees, and $280M raised. Investors included Flatiron, Amazon, and SoftBank (Flatiron’s LP). The problem with Kosmo was unit economics never panned out. Free delivery is expensive, so while the hook attracted plenty of customers, the company was burning cash with high fixed and variable costs. They lost money on literally every delivery.

Flatiron lost more than $25M on Kosmo.

Chase Capital saw enough.

Some difficult discussions took place, and Chase Capital decided to bring Flatiron Partners in house. They wanted more control over their venture capital investments given the volatile environment. Chase was also on the verge of merging with JP Morgan in late 2000, and bringing Flatiron in house was a strategic move.

By 2001, a significant percentage of Flatiron’s portfolio had lost value, and the time spent trying to clean up the mess was no longer worth it. Jerry Colonna joined JP Morgan Partners - the PE arm of the bank - for about 18 months before leaving venture capital altogether. Eventually JP Morgan closed Flatiron Partners permanently.

Fred Wilson would be back. He enjoyed the game too much not to play again. For him, the dot com bust was just an expensive education, a PhD in venture capital.

“That was an incredible learning experience for me. I spent a lot of time thinking about the mistakes we made and what worked and what didn’t work and what kinds of companies worked and what kinds of companies didn’t work and what kinds of investment strategies worked and why they didn’t work. I feel like I came out of it much, much stronger.”

Fred Wilson

A few key lessons he took from that chapter:

The Internet is a two-way exchange. The businesses that made it through the bust were the ones that took advantage of the two way nature of being online. For instance, eBay connects buyers and sellers globally, using the Internet to do something that can’t be done offline. That’s an Internet business that makes sense.

Beware of bad co-investors. Who you invest with matters a lot. There are a lot of venture capitalists who are highly transactional and will gladly throw founders under the bus for a quick dollar. Fred made sure to keep a list of co-investors he wouldn’t be doing business with. His list includes almost every corporate venture capital firm in existence, because Wilson believes they’re not invested in the founder’s success, corporate VCs are invested in their parent company’s interests.

Teams need to be lean and capital efficient. A large $30M seed round is not ideal. It’s best to raise smaller amounts of capital in the early stages and overdeliver, then raise larger amounts when you’ve reached deep product-market-fit in the Series B stage and beyond.

Now it’s on to the next one.

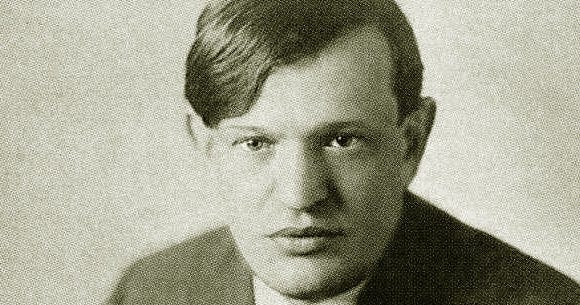

Frigyes Karinthy was a Hungarian author from the early 1900s. His career can be divided into two acts: pre-World War I and post-World War I. In the first act, Karinthy was known for his humorous parodies and translation of Western bestsellers into Hungarian books. He famously translated Winnie the Pooh into Hungarian, and the book would become a cult classic in Hungary. The second half of his career was more serious, focused, and respected by literary analysts. Although he maintained his sharp satire, Karinthy started producing works that deeply explored the human condition, tumultuous relationships, and complementarity between men and women. It was during this time that Karinthy would go on to publish a series of short stories under the title Everything is Different. The most enduring piece of his legacy can be found in a small section of Everything is Different, titled Chain-Links.

In Chain-Links, Karinthy proposed a concept that would change the study of network theory forever: six degrees of separation.

The idea is just as simple as it sounds.

Everyone can be connected to anyone in the world with no more than six connections from personal acquaintances.

“A fascinating game grew out of this discussion. One of us suggested performing the following experiment to prove that the population of the Earth is closer together now than they have ever been before. We should select any person from the 1.5 billion inhabitants of the Earth—anyone, anywhere at all. He bet us that, using no more than five individuals, one of whom is a personal acquaintance, he could contact the selected individual using nothing except the network of personal acquaintances.”

Frigyes Karinthy, Chain-Links

Imagine that.

Run the experiment in your head.

You know someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows the person you’re trying to contact.

In most cases, the link is much shorter.

You know someone who knows someone who knows the person you’re trying to contact.

There’s a sense of freedom in understanding this; everyone you need to know to succeed in any particular game is within arm’s reach.

Or maybe that person is buried in your past.

While Fred Wilson was at Euclid, he led the seed round for a company called Multex.

Multex was a financial information and research distribution platform founded by Isaac Oren - its unique value proposition was digitizing the distribution of Wall Street research.

AT&T Ventures also participated in the round as a co-investor alongside Euclid.

AT&T Ventures would go on to lead the Series A round, and the partner from AT&T Ventures that did the deal was Alessandro Piol.

Piol ended up leaving AT&T Ventures to join Invesco, and a new partner from AT&T Ventures began working with Isaac Oren and Fred Wilson on the board.

This partner’s name was Brad Burnham.

Brad was a much different personality from Alessandro - he was a quiet thinker that kept his fingers on the pulse of the market, skilled in shifting the founder’s story to ride the next wave that would lead to an outsized outcome. His skillset was not necessarily in telling the founder how to do the thing right, but in telling founders how to do the right thing, meaning something the market would reward. Fred, on the other hand, was good at telling the founder how to do the thing right - that is, operate the right way, from hiring decisions to investor communication to dealing with customers. Fred was execution, Brad was high-level strategy.

Isaac was having trouble getting the market response he wanted with Multex, and Brad kept feeding him ideas on how to shift his go-to-market strategy. At one point, Isaac got so sick of hearing Brad repeat his plan that Isaac decided to actually act on Brad’s advice, perhaps to prove him wrong. Unfortunately, Brad’s idea worked perfectly, and Isaac ended up taking credit for it in the press, which Brad didn’t mind.

Multex ended up going public and eventually got acquired by Reuters in 2003.

Fred never forgot the impression that Brad left on him. Aside from singlehandedly changing the trajectory of one of his portfolio companies, Brad’s performance on the Multex deal was a masterclass in equal parts patience, raw intelligence, and humility. Brad embodied all of the characteristics that Fred valued most in a fellow investor.

As things would work out, when Fred was winding down Flatiron Partners, Brad was also winding down at AT&T Ventures. The CEO of AT&T at the time wanted control over his venture arm, and when it became apparent that would not work, he opted to shutter AT&T Ventures.

Keep in mind, Fred and Brad had not worked together or even maintained consistent contact outside of the Multex deal. For whatever reason, Brad contacted Fred to angel invest in one of his portfolio companies, TACODA. Fred, who had nothing better to do at the time, jumped in on the deal, and joined the board with Brad as well.

That was when Fred remembered how pleasant it was working with Brad.

They started talking about teaming up and starting a fund.

“What Brad really taught me was how to do the right thing, which is what to invest in. Like, I said to Brad, ‘we’re just going to invest in the Internet.’ He’s like, ‘but Fred, there’s a lot of Internet. Where are we going to invest?’”

Fred Wilson

Here’s how Brad helped engineer the fund’s thesis.

It starts with a history lesson.

In the late 1980’s through the early 1990’s, a lot of senior partners in venture capital were looking to slowly exit the business and they started to cede control of their funds to the younger partners. Timeline is important here - as the early 1990’s became the mid 1990’s, the younger partners had more control than they were used to and this, combined with the seductive temptations of the dot-com boom, led to the overindexing of Internet businesses across venture capital. So when the dot-com bust took place, the older partners got out of their graves and returned to their thrones in an effort to restore order. Capital flowed away from the Internet (software tech) and back to silicon chips and routers (hardware tech), because the older partners made their money from silicon chips and routers in the 1980’s. So in 2003, when Brad was conceptualizing a fund thesis, he realized that the application layer of the Internet was an open space once again since everyone rushed out after the dot-com bust.

The only thing left to do was come up with a name.

Not many people would double down on the New York theme after experiencing failure with Flatiron Partners. But Fred wasn’t the average person. So he doubled down.

Union Square is a historic neighborhood in Manhattan where downtown and midtown meet. The symbolism is important because Fred and Brad wanted their firm to be the junction where technology and finance met, where Silicon Valley and Wall Street met, and where early stage investing and late stage investing met. Hence, Union Square Ventures was born.

Flatiron Partners walked so Union Square Ventures could soar through the New York City skyline like a Gulfstream G700.

Now the stage was set, Fred and Brad started pitching to limited partners.

Although both firms were named after historic NYC landmarks, USV’s first fundraise was nothing like Flatiron’s cakewalk. Both funds had nearly identical targets: USV was raising $125M and Flatiron’s first fund raised $150M. But Flatiron’s fund was basically closed after a few pitches while USV struggled to get a single yes in their first year of pitching.

“We had people falling asleep in our pitches”

Fred Wilson

“We had people walking out (mid-pitch).”

Brad Burnham

The first 90 meetings were all no’s.

Kind of similar to how Stephen Schwarzmann got 488 rejections while he was raising Blackstone’s first fund. Not as bad, of course. It’s quite remarkable how some of the best funds go through near death experiences at birth. Keep in mind, Flatiron Partners - easiest fundraise ever - was out of business just six years after it closed its first fund.

The ideas that attract capital fastest are not always the ideas that outperform the market.

Fourteen months after Fred and Brad started pitching, nearly one hundred rejections later, they got a call from Lindel Eakman at UTIMCO, the University of Texas endowment system.

UTIMCO would come in for $25M.

The floodgates opened.

“Fred and Brad in 2003, 2004, they couldn’t raise capital. No, everybody hated venture. Brad and Fred had this framework about sort of digital networks and digital natives at the time. And it resonated with me because I was 29 years old. It was a moment where this made sense and they matched. I was probably their ICP, ideal customer at that point who had capital and it resonated with… We were lucky because we were forced to. They wouldn’t let us into the name brands, we were public. Brad and Fred needed money, they weren’t picky about it, and they would take $25M, 20% of their fund from us. Look, if Sequoia had let us in, or Kleiner Perkins at the time had let us in, maybe we wouldn’t have had the appetite for this new set of emerging managers, to be honest.”

Lindel Eakman to Samir Kaji

After UTIMCO, a handful of investors sitting on the fence hopped in.

The State of Oregon, Morgan Stanley, and a few others showed up to the party with everyone’s favorite social lubricant: cold, hard cash.

Union Square Ventures was alive.