Master Gardener: Hostis Publicus

the state of college endowments: MG2.

Previously:

The college endowment industry is a maze.

Better yet, a riddle.

To make sense of the clues, we talked to Jarett Wait.

Jarett has held executive positions at the highest levels of finance.

He worked at Lehman Brothers for many years in various roles, most notably, as CEO of Lehman Asia. He started at Lehman when David Swensen was there.

After Lehman, Jarett helped Fortress build what is now a $45B+ fund. He served as Head of Capital Formation, sat on the Executive Committee, and was a managing director.

He’s raised money from endowments and pensions, is a Council of Foreign Relations member, and sat on the Board of Advisors at a Top 20 college. He is currently the Managing Principal at JF Wait Advisors, a New York based consulting firm.

In order to understand endowments today, one needs to thoroughly understand the college business model.

Start with elite public universities and then we’ll weave our way to the private side.

Public universities make far more money on out-of-state students than in-state students, but are restricted by legislature to admit a certain percentage of in-state students. At the University of Virginia, for example, 67% of each class must come from in-state students. At the University of North Carolina, that number is higher - 82% - implying less favorable cash flows from tuition revenue. So out-of-state students are premium buyers compared to in-state students. International students are the ultimate customer for any college, because they pay full sticker price in cold cash.

Large research universities make money three ways in descending order: tuition revenue, research funding, and donations.

Wealthy alumni - and occasionally wealthy people without ties to a college - donate millions back to their alma mater to get their names on a dorm, basketball court, you name it. The top 5% of donors account for 95% of donations. Donations are almost always earmarked for specific purposes with heavy restrictions around them. The reason endowment donations are so restricted is because the donors have leverage - colleges need to continually bring in more dollars to patch up the deficit. Tuition revenue is not enough.

“The endowment was supposed to be a way to create this evergreen ability to fund, right? To fund whatever it might be they need to fund because the economic model around tuition doesn't pay for the overhead today in the underlying business model of higher education in this country. It just doesn't.”

Jarett Wait to mainstreet.

So what happens when colleges can’t make the business model work?

Take this anonymous top 10 college in 2008 as a case study.

Following the Great Financial Crisis, everyone was financially challenged. Wealthy donors weren’t donating. Parents weren’t able to pay full tuition prices. The endowment portfolio performed poorly and didn’t contribute as much money to operating expenses.

Sidebar: Elite private universities usually spend ~5% of their endowment to help fund operating expenses. For example, a college with a $20B endowment would spend ~$1B of its endowment on annual expenses.

The result of these headwinds was an enormous budget shortfall. Nearly $2.5B in unfunded operating expenses.

The college pulled a couple of strategic levers to cover their debts. Their campus was quite spacious, with undergraduate housing spread out over a large landmass. The first lever was to increase the amount of housing available by financing bonds to cover construction costs as well as plug the deficit directly. Construction would allow them to methodically bring in more students over the coming years. A bond offering of this magnitude meant they needed to come up with a seductive pitch for credit rating agencies.

Increasing student housing capacity → increasing student enrollment + higher proportion of international students + steady tuition increases = a tangible increase of cash flows to cover interest expenses and maintain a high quality credit rating. In 2010, prospective college students could only apply to 10 schools through the Common Application system. By 2016, this number would increase to 20. No conspiracy here, the Common Application is a non-profit organization and its governing board is filled with admissions directors from top private schools. The increase was intentional. More students began applying to highly selective colleges, and in turn, these colleges were able to increase enrollment without sacrificing selectivity. Schools allocated more resources to international marketing, looking to attract students in Asia, who pay cash.

In 2000, international students made up 15% of the student body.

By 2020, that number spiked to 25%.

In 2000, the total student body was ~19,000 students.

By 2020, that number spiked to ~25,000.

Over the course of two decades, the number of students increased 34% and the percentage of international students increased 67%, with a lot of that growth coming during the 2010-2020 period, post-GFC. Not to mention tuition price growth.

This is the business model of college.

Endowments today almost all run on some variation of the Swensen model discussed in “Radices”, investing heavily into alternatives managers running venture capital funds, hedge funds, and private equity funds.

The influence that college endowments have on private markets cannot be understated:

15-20% of all venture capital raised can be traced back to endowments

According to the 2023 NACUBO-Commonfund study covering ~700 endowments, the average college endowment allocates 30% of their portfolio to PE/VC

Elite college endowments sprint past this benchmark: Princeton’s portfolio is 42% PE/VC

In order for a venture capital fund to reach $1B+ AUM, bringing on a college endowment is critical

Endowments are a critical pillar holding up institutional venture capital. Both parties are inextricably linked to each other like co-dependent organisms in the wild. If one dies, the other will eventually cease to exist.

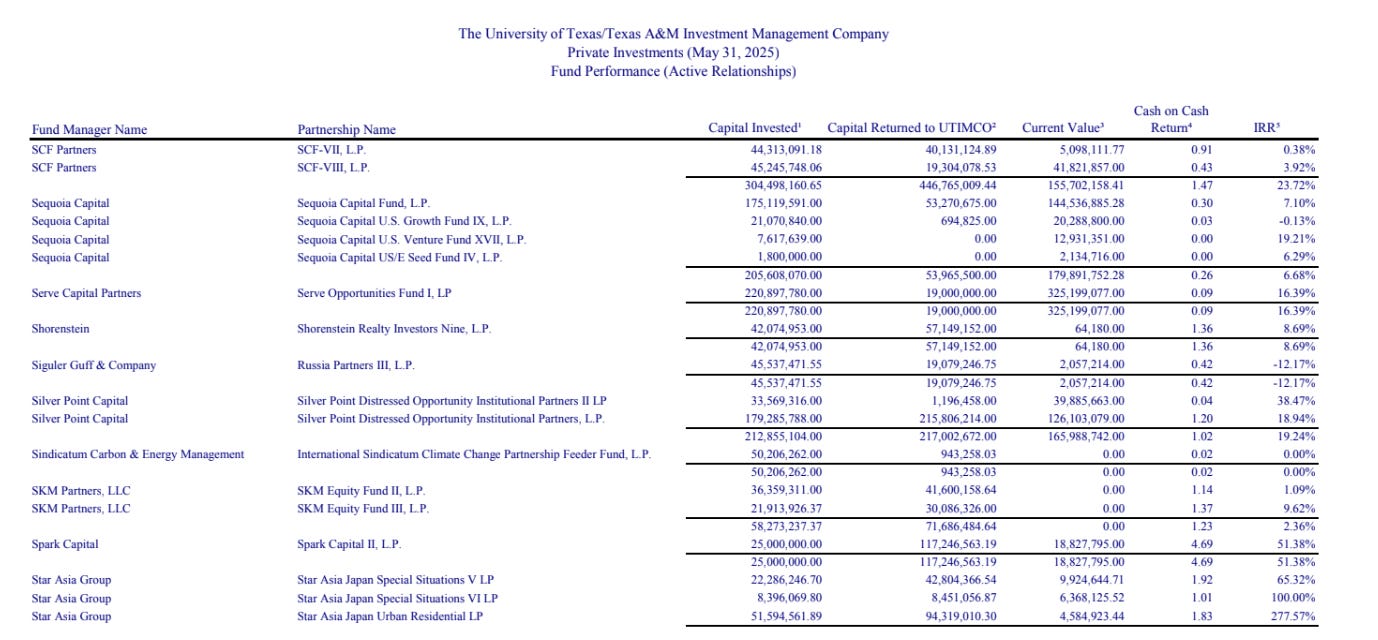

Each large university invests in hundreds of funds in each asset class. Although private endowments keep their books closed to the public, public university systems will disclose their holdings if you make a formal request.

Check out some UTIMCO (University of Texas System) holdings below.

There is no noticeable correlation between size and endowment returns when examining the largest endowments in the world. Certainly, if we looked at colleges with $5B+ in endowment assets versus those with <$5B, we would see that colleges over the cutoff have better returns, namely due to better resources - structured processes, larger investment teams, etc. Nonetheless, a handful of colleges with small endowments ($1B - $5B) demonstrate top of market returns due to specialized investment strategies that larger endowments are unable to replicate at scale.

MIT, Yale, and Princeton are some of the highest returning mega-endowments over the last ten years. Here’s how they invest:

Princeton University:

The Princeton University Investment Company (PRINCO) is one of the largest endowments in the world ($34B), and the richest on a per student basis ($4M). PRINCO is managed by Vince Tuohey and prides itself on being organizationally nimble, allowing staff to retain authority on manager selection without approval for asset shifts. PRINCO employs 24 investment professionals and 30 operations professionals, a total of 54 employees. Their assets to employees ratio is ~$629M to 1.

The endowment targets spending between 4% - 6.25%, and that mark landed at 5.04% in 2024, or $1.7B.

Asset allocation as of 2024:

Private Equity: 42%

Absolute Return / Hedge Funds: 26%

Public Equity: 18%

Real Assets: 10%

Fixed Income / Cash: 4%

PRINCO’s annualized ten year return is 9.2%, making it one of the top endowments in the world.

Yale University:

Yale Investments is led by Matt Mendelsohn and manages a pool of $41B. The office employs 48 professionals, including 25 investment professionals. Their assets to employees ratio is ~$854M to 1.

Yale aims to spend 5.25% of the endowment each year, which equates to roughly ⅓ of total operational expenses. Yale spends about half of the total endowment value every decade. The endowment contributed $2.1B to operational expenses in 2025.

Asset allocation is as follows:

Private Equity: 38%

Absolute Returns / Hedge Funds: 22%

Fixed Income / Cash: 14%

Public Equity: 14%

Real Assets: 12%

Over the past ten years, Yale’s endowment returned an annualized 9.5%, and 10.3% over the past twenty years.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

MITIMCo is led by Seth Alexander and manages a pool of $24B. The office employs a lean team of ~15 for their investment size and an unknown amount across the board. Assuming an average multiple of 2.2x total employees to investment professionals, the total number of employees is roughly 33. This means assets to employees ratio is ~$727M to 1, second only to Yale. An interesting facet of MITIMCo operations is the flat, generalist structure. Investment decisions are made by teams of 3 to 4 and all team members are free to determine how to spend their time. Each team member outside of the CIO has the same title, description, and work across asset classes and geographies. The endowment marketing copy claims “it is more like working at a venture capital partnership (than an endowment)”.

MIT’s effective spending rate is 4.8% average on a three year basis. It works out to around 30% of operating expenses and came out to a little under $1.5B in 2024.

Asset allocation is as follows:

Private Equity: 36%

Public Equity: 22%

Absolute Returns / Hedge Funds: 16%

Real Assets: 16%

Fixed Income / Cash: 10%

Over the past ten years, MIT’s endowment returned an annualized 10.5%, making it the only mega-endowment to post double digit returns during that time horizon.

The average asset allocation profile for these top performers looks like this:

Private Equity: 38.7%

Absolute Return / Hedge Funds: 21.3%

Public Equity: 18%

Real Assets: 12.7%

Fixed Income / Cash: 9.3%

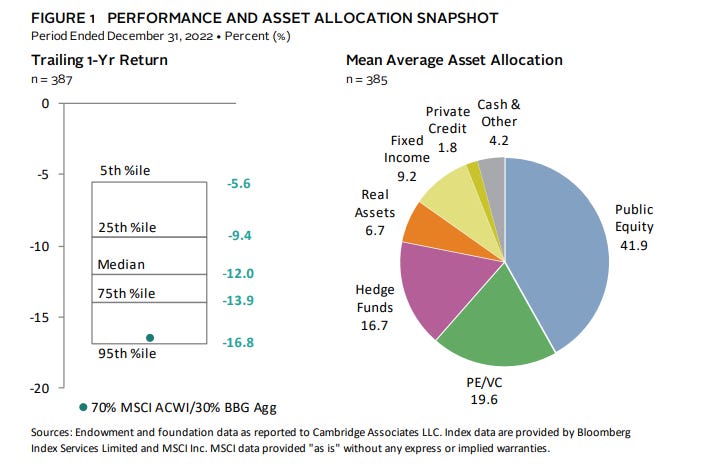

Compare that to the average college endowment, per Cambridge Associates (n = 385)

Public Equity: 41.9%

Private Equity: 19.6%

Absolute Return / Hedge Funds: 16.7%

Fixed Income / Cash: 15.2%

Real Assets: 6.7%

For all the hustle and bustle, every single one of these elite endowments underperformed the S&P 500 - 12.5% annualized over the past decade - significantly.

One donor at a large public university couldn’t stand that.

Clarence Herbst was a three time varsity athlete at University of Colorado, Boulder. He graduated from CU Boulder in 1950 with a degree in Engineering before taking the CEO role at Resinoid Engineering, a company his father founded in 1900. Resinoid is now in the third generation of Herbst ownership. The company consists of two unified manufacturing divisions integrating phenolic compound raw goods, compounding of phenolics, and custom molding.

The Herbst family has been a major philanthropic contributor to CU Boulder, funding projects such as the Herbst Academic Center in the Dal Ward Athletic Center, the McCord-Herbst Student Veterans Center, the Herbst Humanities Program in CU Boulder’s College of Engineering, and other projects.

In 2020, after having personally donated more than five million dollars to the University, something snapped. Clarence Herbst Jr. sued the college for lagging the S&P 500. Jack Finlaw was the endowment head at CU Boulder, managing a $2.4B portfolio at the time. Safe to say, he did not appreciate the dramatic action: “He has carried this banner for decades… While people can have various opinions on active versus passive investing, it really doesn’t rise to a legal issue.”

Herbst’s complaint was that unwise and unlawful investment decisions have cost CU students, faculty, alumni, donors, and Colorado taxpayers approximately $1B in potential investment returns. From the Institutional Investor: “Even in the face of a global health pandemic, and what appears to be another recession, the index funds advocated for by plaintiffs are almost certainly trouncing the CU Foundation’s expensive, fee-laden, actively managed, and alternative-investment-dependent investments… Defendants’ refusal to invest a substantial percentage in low cost, passive index funds has likely cost the university tens of millions of dollars thus far in 2020.”

The argument against Herbst would probably mention the volatility of public market exposure and the superiority of private equity returns over a longer term horizon. Endowment managers would argue that public market exposure is too volatile to support the 5% spending rule from college endowments. If the public market takes a 37% hit like it did in 2008, we’d be unable to support the university’s operating expenses using the endowment. Seems like a decent argument at first glance, but in 2008, college endowments had heavy private equity exposure and were generally unable to support their operating expenses regardless. Public markets are liquid, so you can reduce exposure and get cash in return. There is no such option on the private side. We’ll table the returns argument for now.

At its core, Herbst’s argument is deeper than returns. It’s about clearing out the noise, whittling down the fat, turning on the lights. What is the primary purpose of an endowment? Why are we investing in managers that, on net, underperform equities, a less risky asset class than PE/VC/HF? Who is winning here?

The college endowment industry is a riddle.

Better yet a maze.

The problem with investment teams at endowments is a lack of aligned incentives. The money doesn’t add up the way it should. Harvard’s endowment head made $15M at Harvard in 2015 after under-performing his Ivy League peers. He was public enemy number one when the information became public. But he’s not alone. The University of Virginia endowment head made $7.6M last year after delivering a 1.9% annual return. Another UVA investor got paid $4.4M for contributing to their losing year. The S&P 500 finished at 25%. Billions of dollars in value were left on the table and people got rewarded. How does that work? Let’s dissect it, piece by piece. The endowments all flocked to the Swensen Model after 2000, when money began gushing in from venture capital and private equity. The boards of endowments got filled with private equity and hedge fund executives. The endowment managers - CEOs, CIOs - are clearly incentivized to follow the Swensen Model. If an endowment head says, “Hey, let’s index heavily to the S&P 500, get some fixed income exposure, and remain opportunistic on alternatives”, he would be fired, because you can’t justify a multi-million dollar salary for indexing to the public markets. That costs nothing. Allocating half of the portfolio to complex private investments allows allocators to justify their compensation. The final piece of the puzzle is the investment consulting industry. Large, shadowy organizations provide the research and advisory services so that managers maintain information asymmetry relative to the constituents they serve.

Finally, when the endowment manager has fulfilled their obligation, they get poached by one of the firms they invested into. Or a firm that has an executive on the endowment board. And the next endowment manager might come from a firm that the endowment has already invested in. The revolving door concept extends past politics… The Brown University CIO/CEO from 2013 to 2020 got hired by Blackstone as a Senior Managing Director in 2021.

An endowment manager is not a true investor; the role is closer to holding political office than beating the market.

Endowment investing is not a competitive sport. Innovation is discouraged.

“If you're going to outsource your money and you're a pension fund, you're an endowment, you're a foundation, you have any money, you have any fiduciaries, the first thing that you want to do is you want to make a good decision. You don't make a good decision, you're going to be subject to being canned by your board. So, what do you do? You go hire a consultant who does this. The consultant sits down with you and they figure out what your investment strategy is and then they act on your behalf. They might even put out an RFP to invite managers to pitch for the business and then the consultants basically will say this fund has been approved by us. So, I guarantee you there are consultants that work with Harvard and Yale and Cornell and they are also the consultants that work with the managers themselves and they're extremely powerful and they're a key constituency in the whole puzzle… those institutions play an incredibly important role because they're not only gatekeepers, but they're also toll collectors. Like they can put the gate down, but then they can also open up the easy pass lane.”

Jarett Wait to mainstreet.

Nearly every high stakes industry - basketball, football, music, filmmaking - has some variation of the principal-agent problem.

By definition, the principal-agent problem occurs when a principal/owner delegates tasks to an agent/manager who may not always act in the principal’s best interest.

The principal relinquishes his agency, or power, to the agent, due to a lack of information. Information asymmetry is the agent’s single great advantage; without information asymmetry, the agent fails to exist.

The most lucrative principal-agent problem can be found in institutional investing.

While an NBA agent makes money from his client’s contract - one side of the transaction - investment consultants typically collect a gatekeeper’s fee from every participant in private markets. The endowments pay them to find funds and construct portfolios, and the fund managers pay them for access to endowments and visibility in the market. Even the federal government will toss them a bone from time to time - in 2008 the US government brought in a well known investment consultant shop to find fund managers that could manage distressed assets post-GFC. And the investment consultant with the mandate had never seen a distressed cycle before. These guys collect fees large enough to make even the fattest cats purr softly.

Investment consultants are not McKinsey, Bain, and BCG. We’re talking about Aon (fka Hewitt EnnisKnupp), Mercer, and Cambridge Associates.

These guys are the intersection through which private capital flows.

They help endowment executives keep the party alive.

To go further, the principal-agent problem in institutional investing is multi-layered. Endowment managers are middlemen with misaligned incentives who bring in third party consultants with misaligned incentives to continue the cycle. All while burning billions of dollars in value. Swensen was innovative and his model worked because no one else was doing it. Now everyone is doing it, and multiple layers of middlemen take bites of the pie before it gets to the table.

When Clarence Herbst sued the University of Colorado, this is what he was getting at. The lack of aligned incentives. The political bureaucracy embedded within the business of college. Hidden motives and deep rooted deceit. His disgust was deeper than investment returns. It stemmed from seeing an institution he loved so dearly embrace corrupt practices that left constituents worse off.

Herbst is not alone.

Marc Andreessen, founder of a16z, told a group chat that Stanford will pay the price for forcing his wife out as a chair of the Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society. Andreessen said Stanford “forced my wife out without a second thought, a decision that will cost them something like $5 billion in future donations.” Andreessen has donated millions to Stanford in the past.

Kenneth Griffin, founder of Citadel, publicly stated that he will not donate any more money to Harvard. The prominent hedge fund founder is one of Harvard’s most prolific donors, having donated more than $500 million to Harvard over the past forty years.

Remember how important these donors are - the top 5% of donors make up 95% of donations.

In 2024, Harvard’s donation total fell by ~$200M relative to 2023.

President Trump continues to apply pressure on Harvard, with federal funding freezes and verbal abuse.

Harvard recently issued a $450M bond offering in the midst of a challenging environment, increasing its total debt load to $7.6B, a 22% increase over the past two years. Annual expenses now come out to $6.5B, just a hair short of expenses generated at Blackstone. 52% of that $6.5B goes to paying people at the University.

An endowment tax hike looms on the horizon, replacing the 1.4% rate to an 8% tax on investment income. The new policy is projected to cost Harvard $250M+ a year, starting in 2027. If Harvard is taxed at the endowment gains rate discussed in Congress in May (21.4%), they would pay $850M annually on an average investment gain of 7.5%. An endowment tax this high would result in lost income of more than $4.25B over five years, which Harvard would struggle to recover from. Harvard and Yale are currently selling off chunks of their portfolio on the secondary market. Multiple large endowments across the board are going through the same exercise, with some even remaining quiet about their dealings. For instance, the University of Virginia has publicly stated that they are not looking to sell assets, but our source at a large secondary buyer (HarbourVest / AlpInvest) says otherwise.

Ivory towers stood tall for centuries, but now they look unstable. A heritage once inherited is being marked down to avoid estate tax. Not to fear, crises often gift creativity for revival. Survival instincts kicking in, the restructuring will be internal. Before we jump out the window, please unlock this paradox:

What is a college’s primary asset?