Master Gardener: Radices

a deep sea dive into the history of endowments: MG1.

Advertising is a business of words, but advertising agencies are filled with men and women who cannot write.

David Oglivy.

Modern endowment investing is a much newer concept than you’d think.

The now trillion dollar industry sprung from a small seed in the early 1900s.

Paul Cabot was born in 1898 to a wealthy family in the Boston area. Wealthy and powerful, to be precise. The Cabot family was known as one of the “Boston Brahmins”, a term that crowned the ruling class of the Boston area. Other Boston Brahmins include the Adams family, the Bolyston family, the Eliot family, the Lowell family, and a handful of others. Each had their names on various dorms, libraries, and halls on Harvard’s campus. Each sent all of their children to Harvard, of course.

John Collins Bossidy’s Boston Toast sums it up well:

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk only to the Cabots,

And the Cabots talk only to God.

At Harvard, Paul joined the Porcellian Club, the most prominent secret society on campus. Theodore Roosevelt is their most famous member. The Porcellian motto is “Dum Vivimus Vivamus”, a Latin cry to embrace hedonism. While we live, let us live. Cabot put a golden pig on his watch chain as a perpetual reminder.

During college he developed a reputation as an intelligent troublemaker. In 1918, towards the end of his freshman year, Paul had some friends over at his dorm during a dance in the Yard. Prompted by his comrades and a little bourbon, Paul decided to whip out his ROTC rifle and fire a blank into the party below.

All the little girls thought the Germans were out for them. I let go another round. [The proctor] caught me with the rifle with the smoke coming out of the barrel. Luckily my friends kicked the booze under my bed… I knew I was in major trouble.

Paul Cabot to Harvard Magazine, Jan. 2003 edition

His father made a plea to a close friend, Harvard President Lowell, and Cabot beat the case.

Paul graduated from Harvard College and then Harvard Business School before joining the First National Bank of Boston in London. He hated his boss and lasted just six months. While in London, however, Paul intermingled with J.P. Morgan’s grandson, who introduced him to Robert Fleming, a friend of the Morgan family. Fleming taught Paul about the Morgan’s inner dealings. Morgan’s success, according to Fleming, came from his constant meetings with railroad managers, which allowed him to accurately assess which railroad stewards were the sharpest and lend money to them. Information was the asset, and when it came to railroads, Morgan was the intersection through which all market knowledge flowed.

Cabot came back to America enlightened.

In 1924, he founded State Street Investment Corporation alongside two other Harvard alums with the same first name: Richard Paine, his cousin, and Richard Saltonstall, his close friend. The fundamental thesis was that other investment corporations were not meticulously collecting information on the companies they were investing into. SSIC would be one of the first companies to conduct extensive due diligence on investment targets by visiting companies and interviewing managers to find an information edge.

Their efforts were fruitful to say the least. From 1924 to 1929, SSIC returned 434%, more than twice the market average. Paul Cabot was just 31 at the time. State Street Investment Corp continued to grow in influence, capital, and prestige.

The latter half of the 1920’s was quite a time.

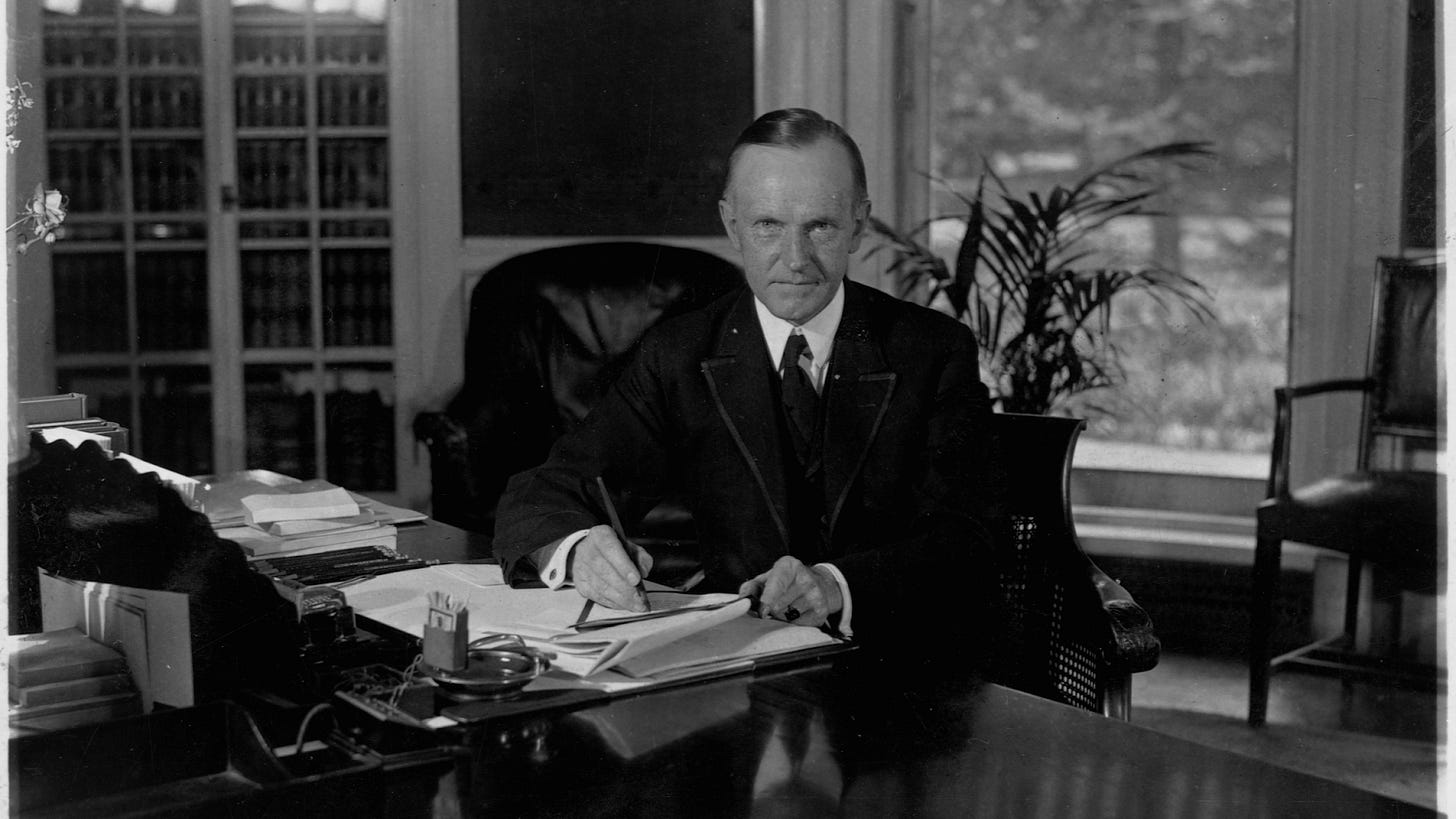

President Calvin Coolidge was in office.

Charles Lindbergh completed the first nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris.

Al Capone was running the Prohibition underworld.

The Roaring Twenties saw a drastic increase in consumerism and entertainment culture. Radios became household items. Cars became affordable for the masses via Ford. Jazz music and movies became popular and widely available. Most importantly, the pain from World War I inspired a nationwide desire to buy like tomorrow didn’t exist. For the first time in American history, people were spending money they didn’t have on things they didn’t need. Household debt levels surged.

A decade of uninhibited elation was capped off by the Great Depression.

Cabot and his colleagues at SSIC navigated the market crash like veterans. The fund’s focus on fundamental analysis and healthy companies allowed them to avoid the worst of 1929. His network of ultra-wealthy Bostonites strengthened during this time. His research oriented approach preceded even Benjamin Graham and the like. Paul began to educate lawmakers on Capitol Hill who wanted to understand more about the markets after the fact.

I know. This has nothing to do with college endowments.

Harvard’s endowment was virtually nonexistent at the time. There was no Harvard Management Company, internal investing team, asset allocation strategy, or even public equity holdings. Harvard’s portfolio was exclusively land, fixed income, and cash. A Treasurer from the board oversaw the holdings, but the position was a part-time one, and the Treasurer was often occupied with his day job either running a fund or a national bank.

In 1948, Paul Cabot was appointed Treasurer of Harvard University, and as part of his contract, Harvard agreed that the endowment portfolio would be managed by State Street going forward. This means, even when Cabot decided to step down from State Street, State Street’s next President would preside over Harvard’s endowment. State Street would be inextricably linked to managing Harvard’s assets. In exchange, Harvard would pay State Street $100,000 per annum.

Cabot’s first order of business as endowment head was to introduce equities into the mix. As mentioned previously, the University only invested in land and fixed income. Equities was widely considered a risky asset class. In the broader landscape of institutional investing, a few forward thinking endowments were starting to dabble in stocks. The earliest recorded example came from across the pond, when John Manynard Keynes rebalanced the King’s College portfolio from land and cash to an equities heavy asset mix. In America, Cabot was the first university treasurer to buy stocks en masse. Harvard’s head start paid off handsomely in the long term.

State Street would manage Harvard’s endowment for nearly four decades.

After Cabot stepped down, George Bennett, another Harvard College / Harvard Business School alum, stepped up. Bennett was President of State Street, and by extension, Treasurer of Harvard’s endowment. He continued Cabot’s legacy of deep research into undervalued equities, and State Street made $3.6M during its tenure as Harvard’s financial steward. For clearer context, State Street made the equivalent of ~$36M today over a 36 year horizon - about ~$1M per year in today’s dollars. By 1974, the endowment was valued at $1B, and it no longer made sense for State Street to manage Harvard’s assets, especially at a $100,000 price-tag.

Walter Cabot took over the Harvard endowment in 1974, forming the Harvard Management Company, a non-profit entity that still manages the endowment today. Walter - while not a direct descendant of Paul Cabot - came from the storied Cabot lineage that seemed to rule Boston. As he sat alone in an office on 60 Congress St, he wondered how he was going to manage.

I was the only employee, sitting around a lot of packing boxes, and asking: What has the corporation done to me?

Walter Cabot to Harvard Gazette

This was arguably the inflection point for endowments. A billion dollars in assets. It’s easy to lose sight of purpose while pursuing growth at all costs. After all, what gets measured gets managed. Much easier to track assets under management than something elusive like purpose and impact. In all seriousness, what is an endowment’s purpose? Each elite educational institution preaches a dual approach to investing: (a) provide material support to the university’s operations and (b) provide long term endowment growth for future generations. But what happens when operational costs swell to meet new endowment growth? What happens when endowment growth no longer serves future generations of students, but instead inspires gluttony and waste that leaves the organization bloated? What is a college’s primary asset?

In Mad Men’s “The Summer Man” episode, Don Draper pens a soliloquy that would make Oglivy swell with pride. The episode is located precisely in the middle of the series, a detail that cannot be dismissed as happenstance, but rather, an intentional inflection point marking Don’s drowsy descent into vice.

“When a man walks into a room, he brings his whole life with him. He has a million reasons for being anywhere. Just ask him. If you listen, he'll tell you how he got there, how he forgot where he was going and that he woke up. If you listen, he'll tell you about the time he thought he was an angel or dreamt of being perfect. And then he'll smile with wisdom, content that he'd realized the world isn't perfect. We're flawed because we want so much more. We're ruined because we get these things and wish for what we had.”

1970 - 2000 is when colleges forgot where they were going.

In 1975, a Midwestern college student named David Swensen was getting ready to graduate from University of Wisconsin-River Falls, a school just down the road from his childhood home - partially because his father was a professor there. Swensen went on to do a PhD in Economics at Yale, working under James Tobin, a Nobel Prize winner for his contribution to Modern Portfolio Theory.

After the time at Yale, Swensen went the Wall Street route and spent time at Salomon Brothers, then Lehman. No more than five years after leaving Yale, he returned to his graduate school alma mater assuming he would be taking a job in academia. To his surprise, he was asked to lead the endowment, a $1B pool of capital at the time. Swensen was only 31.

His lack of experience allowed him to analyze the university’s returns model under a different light.

Rather than adopt a 60% equities / 40% bonds model, he looked to alternative assets for enhanced long term returns.

The underlying reasoning was simple: our time horizon is infinite, the university’s endowment is a perpetual vehicle.

Nearly identical logic to Paul Cabot, former Treasurer of Harvard’s endowment. The only difference is by this time - 1985 - equities were much more commonplace. Venture capital, private equity, and hedge funds, were the new standard for cutting edge risk. Private markets were unexplored territory for endowments and Swensen decided to venture onwards into the jungle.

Swensen’s first task when he was appointed in 1985 was to reduce the heavy reliance on public market exposure. When he came into office, around 80% of Yale’s portfolio were public stocks and bonds.

From 1986 to 1988, he made the endowment’s first venture capital picks, investing in Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins, two emerging managers in the space.

During 1990 to 1992, alternatives made up nearly 50% of Yale’s portfolio. He started deploying more aggressively to hedge funds, including Soros Management, Tiger Management, and Lone Pine Capital.

Swensen’s focus in alternatives / private market exposure was manager selection. He wanted to form high quality, long term relationships with the best managers of tomorrow. In addition, he wanted to keep fees low to preserve compounding returns. His due diligence process and monitoring framework was considered rigorous at the time: he met with managers at least five times before committing capital, often taking months and in some cases, more than a year to build trust. The final pillar to his philosophy was to keep his team small. Yale’s endowment had an internal investment staff of around 20 people focused on risk management, asset allocation, and manager selection.

In the late 90’s (1995 - 1997), the early venture capital bets began to pay off. Amazon, Google, and Yahoo all provided liquidity in the form of IPOs, and venture capital became Yale’s highest returning asset class.

Yale was almost ten years early to the party.

From 1985 to 2000, Yale notched a 16% IRR, performing in the top 1% of endowments.

By 2000, almost every elite academic institution had exposure to venture capital.