Ubiquitous I

uber everywhere.

Friedrich Greiner knew there had be a better way to hail a ride.

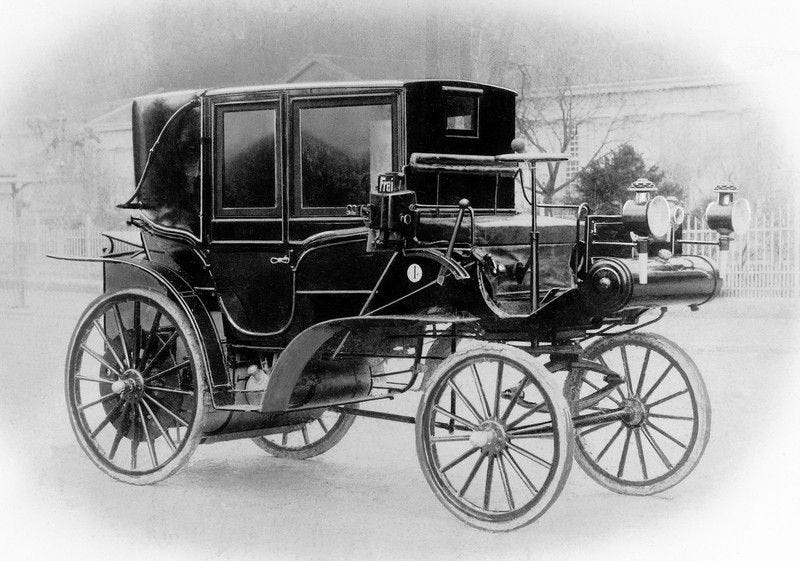

Greiner was a German entrepreneur that ran a carriage rental business in the late 1890s. He understood that the maintenance required by horses far exceeded the relatively consistent cost of maintaining a motor vehicle. He eventually built the Daimler Victoria in 1897—a motorized carriage that hit a top speed of roughly 12 miles per hour. While the engine was a necessary step in the right direction, the real innovation was the taximeter, patented just six years prior. Not only did the device measure both distance and waiting time, but most importantly, it eliminated the need for drivers and riders to constantly haggle over prices. The first taxicab (taximeter + cabriolet) had just been born.

They quickly spread throughout Europe and reached New York City in 1907.

Over time, taxis morphed into what we think of them now: the yellow coat to make them more conspicuous was added in 1920, standardization of medallion and licensing systems was added in the late 1930s, and more modern innovations like credit card acceptance, GPS navigation, and early online booking were added within the past three decades.

But just like the carriage system, it was vulnerable to disruption.

Travis Kalanick—Uber’s founder—was the man for the job. More specifically, he wanted to utilize the new technology of the iPhone to kill the old ways of transportation.

There was just one problem: although his product was 10,000 times better, transportation officials are beholden to legislators, and legislators are beholden to donors and lobbyists like driver unions and Big Taxi.

Portland was a perfect example.

The city’s bureaucracy was not going to let Uber enter into their city and set up shop. But Kalanick knew this, so he hired David Plouffe, former political advisor for Obama, to woo the mayor, Charlie Hales, and transportation department head, Steve Novick, and let Uber co-exist with the current taxi system.

Kalanick knew an environment where the two could “co-exist” would inevitably lead to Uber’s domination.

Despite Plouffe’s political skill and persuasion abilities, Novick and Hales weren’t budging. The iron triangle between transportation officials, legislators, and lobbyists proved to be impenetrable.

Get your company out of my ( ) city!

Steve Novick

Plouffe came back to Kalanick and delivered the news.

Kalanick was unfazed and simply nodded: out of the kindness of his heart, he tried the “nice guy” way. But Uber wasn’t set up for the nice guy method…they had already run into this problem in numerous cities.

Their GTM was to blitz both sides of the marketplace (riders and drivers) with a variety of incentives to use the product and get just enough rides going to where it was nearly impossible for local authorities to track or control it.

They would also implement lines of code into their software that made it nearly impossible for local officials to bust Uber drivers.

More on this in the next episode.

This battle against local politicians, the taxi lobby, and transportation officials was one of several battles that Kalanick was facing–but he didn’t mind.

In fact, he embraced them.

There was nothing more that Kalanick enjoyed more than winning a fight or competition.

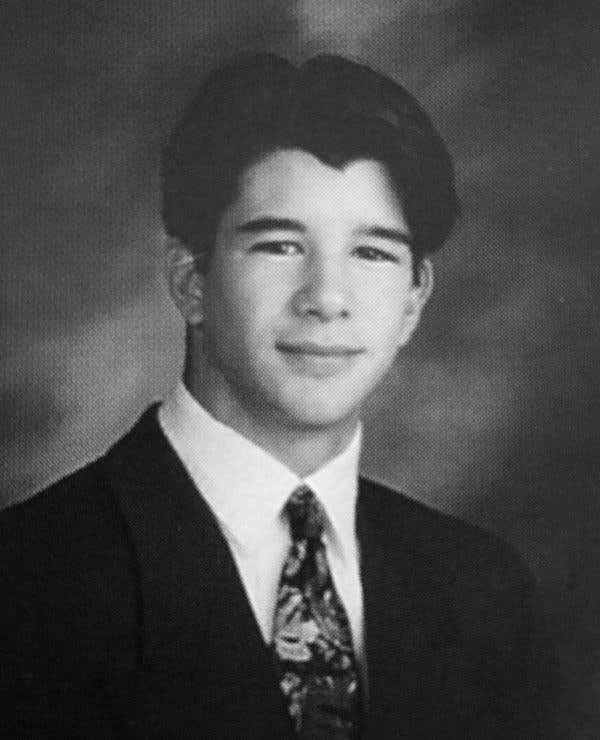

Kalanick was raised in the LA area by his father, a civil engineer, and his mother, a newspaper saleswoman.

This proved to be a perfect combination, as he took his father’s analytical, math based approach and his mother’s ability to sell, as evidenced by scoring a 1580 on the SAT and selling $20K worth of CutCo knives as a teen.

After matriculating at UCLA and studying economics and computer science, he dropped out his senior year to build a company with six of his classmates called Scour, a centralized peer-to-peer file sharing hub.

While many labelled Napster as their main adversary, the crew didn’t necessarily view them as competition, as Napster strictly focused on music files.

Scour was eventually introduced to a few notable investors like billionaire Ron Burkle and Michael Ovitz, the founder of CAA.

A few conversations later, the duo gave Scour a term sheet. The only catch was it came with no shop clause, meaning they couldn’t seek funding from other investors while negotiating.

This proved to be problematic, as the negotiations stalled due to disagreements, and Kalanick and crew wanted to void it so they could source funding and keep their company alive.

After Ovitz caught wind that the Scour team may have been speaking to other investors, he slapped the company with several lawsuits, forcing them to agree to Ovitz’s terms of roughly $4M in funding for 51% of the company.

Unsurprisingly, the partnership wouldn’t last long.

Hollywood began to sue Napster and Scour into oblivion, causing Ovitz to quickly distance himself and task investment bankers with selling his stake in the company.

Soon after, Scour would file for bankruptcy and close its doors.

This provided Kalanick with a clear lesson he would always keep top of mind.

Never trust investors.

Always maintain control.

Kalanick moved on to his next venture, RedSwoosh, a B2B peer-to-peer file sharing company that provided enterprise clients with a faster and cheaper option to distribute large files to customers.

After several close calls with bankruptcy, he caught a break - Mark Cuban extended a $1.8M investment that allowed him to keep going. Shortly after, Kalanick sold the company to Akamai for $20M, netting himself $2M after taxes. Cuban recalled hating the product but loving Travis’s hustle.

Kalanick’s next move would be the best one.

Contrary to popular belief, the ride-sharing app actually wasn’t his brainchild; the idea came from an entrepreneur named Garrett Camp.

Camp had recently sold his startup StumbleUpon to eBay for $75M after raising just $1.5M. He described the platform as “a prototype Reddit…a link aggregation site that at its best delighted users with new, interesting facts, obsessions, and subcultures.”

Camp couldn’t stand the taxi system and instinctively knew he could make the process more efficient.

The original inspiration came to him after watching a James Bond scene where he was using a GPS navigation tool on his phone.

While Camp was coming up with the initial prototype for Uber, Kalanick was transitioning from founder to an angel investor / advisor. He would routinely have founders visit him in his apartment—called the JamPad—where they would discuss MVPs, business models, raising capital, and more.

One of those founders who stopped by was none other than Camp, who pitched the idea of '“UberCab” to him.

Instead of the “anyone can drive anyone” model that we’re accustomed to, the initial concept was a luxury black car service for high-end professionals in the Bay Area, given the high density of young, wealthy white-collar workers in the area.

Kalanick loved the idea except for one part: he didn’t want the company to own the vehicles. After ironing out some details, they were in a good spot to officially get the company off the ground… But neither of them wanted to run the company.

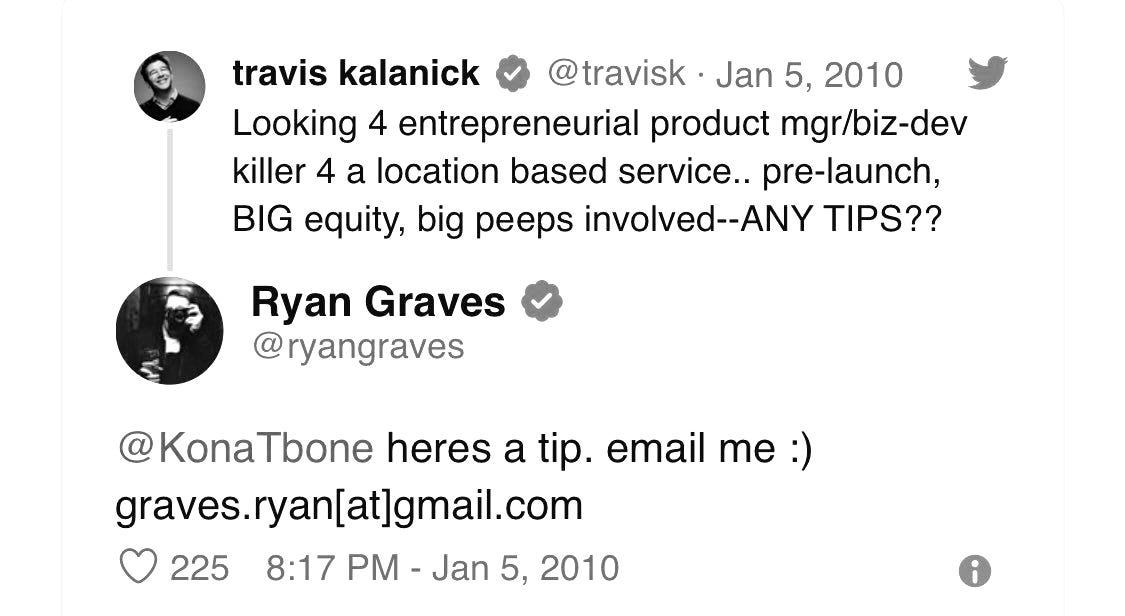

So, Kalanick did the only thing that made sense in his mind: hop on Twitter and see if he could find the right person.

Graves didn’t have any real founder experience under his belt.

In fact, the only relevant experience he had in the space was getting rejected from a job at Foursquare. But rather than accepting defeat, he went to restaurants and pretended that he worked for the company and signed them up for the service. After doing so, he came back to Foursquare with his results: 30 signups from bars and restaurants. Unsurprisingly, they added him to the team, signing him as an intern in their business development group.

Despite his inexperience, Kalanick admired Graves hustle and had a good feeling he’d be the right one for the job.

Turns out, to be a successful founder, hustle is necessary but not sufficient.

He simply didn’t have the “it” factor and had a hard time closing on capital from investors.

Kalanick, understanding this was a now-or-never moment, flipped his sentiment and realized that if this company was going to be successful, he would have to be the captain of the ship.

He thanked Graves for his service and relegated him to be VP of business operations.

Ubercab.com was soon up and running, with rides being 50% more than taxis due to their luxurious nature, as well as the reliability and convenience.

What really changed the game for “UberCab” was the transition from their website to an app.

Of the numerous questions that founders regularly receive, one of the most popular is “why now?” For Uber, this may have been the easiest to answer.

Steve Jobs had recently developed the revolutionary iPhone and, more importantly, eventually allowed third party apps to be stored on the device.

Although he changed his mind after a while, he wasn’t originally a big fan of the idea.

JOHN DOERR (KLEINER PERKINS PARTNER): Steve, I’ve got an idea–I’ll raise a massive fund to invest in aspiring founders building tech companies and we’ll funnel the best ones to be apps on the iPhone.

STEVE JOBS: No, stop right there. I don’t want a wave of ( ) apps from outsiders polluting this phone. Not going to happen.

This development of allowing companies to distribute their software directly to iPhone users perfectly fit Uber’s dream vision.

Uber also had to change their name from UberCab to Uber to avoid regulatory scrutiny from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

Now that Uber had the founder, branding, vision, and distribution set in place, they were ready to test the product-market fit.

Their game plan for attracting drivers consisted of buying hundreds of iPhones with Uber pre-downloaded in bulk at a discounted price and giving them away for free.

They also provided a handful of incentives and bonuses for hitting a minimum number of rides per week.

For riders, the first several rides were often provided at steep discounts, enticing users to spread the word and fuel Uber’s organic growth.

And boy, was their growth off the charts.

Uber was an instant hit in the Bay Area.

However, there is an infamous euphemism in Silicon Valley that rang especially true in Uber’s case:

“Mo’ growth, mo’ problems.”

Uber’s primary growth-related obstacle was transportation officials.

San Francisco bureaucrats arrived at their office and handed them a cease and desist letter. Even worse, they would face fines every day they remained open of up to $5,000. But it didn’t stop there. If they still didn’t cooperate, they would face jail time.

Graves and Austin Geidt, head of GTM in other cities, were shook and thought it was the end of the business they had worked so diligently to build.

Rob Hayes, First Round Capital partner and Uber board member, was shocked, as his portfolio companies had never been in this situation.

Kalanick, on the other hand, kept cool, calm, and collected.

When Graves asked Kalanick what they were going to do, he responded with three simple words:

KALANICK: We ignore it.

Kalanick was a competitor and he was not going down without a fight.

And the fight was just getting started.